I recently read some papers which, albeit apparently unrelated, should be of interest for many today.

Mixed language

The myth of the mixed languages, by Kees Versteeg, in Advances in Maltese linguistics, ed. by Benjamin Saade and Mauro Tosco, 217-238. Berlin and New York: Mouton de Gruyter, 2017 [uncorrected proofs]

This paper focuses on the usefulness of the label ‘mixed languages’ as an analytical tool. Section 1 sketches the emergence of the biological paradigm in linguistics and its effect on the contemporary debate about mixed languages. Sections 2 and 3 discuss two processes that have been held responsible for the emergence of mixed languages, code switching and extreme borrowing. Section 4 compares these two mechanisms with the categories of change in Thomason & Kaufman (1988), while Section 5 offers some conclusions about the status of mixed languages as a special category.

Although the paper is a must read for language contact and language change (code-switching, borrowing, shifting), a good summary may save you some time if you are not interested in linguistics:

Speakers may either shift to a new language while retaining traces of their old language, or they may stick to their original language while borrowing from another language with which they come in touch (…)

[Bakker] distinguishes two types of communities in which mixing is found: isolated mixed marriage communities with (asymmetrical) bilingualism; and nomadic communities that shift to a dominant language, but retain a substantial part of their lexicon as a private or secret register, closely connected with the community’s identity. The history of these communities provides us with plausible scenarios to explain the idiosyncrasies of the speech pattern of the speakers belonging to them.

In what way, then, does it help to put both categories under one label of mixed languages? I believe Backus (2003: 263) is right when he suggests that the question of whether a certain set of features constitutes a mixed language is perhaps not a very interesting one. The question should not be whether given certain features a language may be categorized as mixed, but what the linguistic effects of different kinds of contact (trade, work, conquest, mixed marriages, colonization, marginalization, etc.) are, and to what extent these effects correlate with the type of contact. At no point is it necessary to posit a category of mixed languages. In fact, the myth of the mixed languages may have been perpetuated because of the relative weirdness of the initial cases, notably that of Michif, which represent phenomena so unique that it is understandable that some scholars came to believe that they could only be explained by special mechanisms. The position taken here is that if we focus on the speakers’ behavior, the phenomena in question become much more understandable. The crucial point is that languages do not mix, people do.

Culture core and package

The article Isolation-by-distance, homophily, and “core” vs. “package” cultural evolution models in Neolithic Europe, by Shennana, Crema, and Kerig (2015):

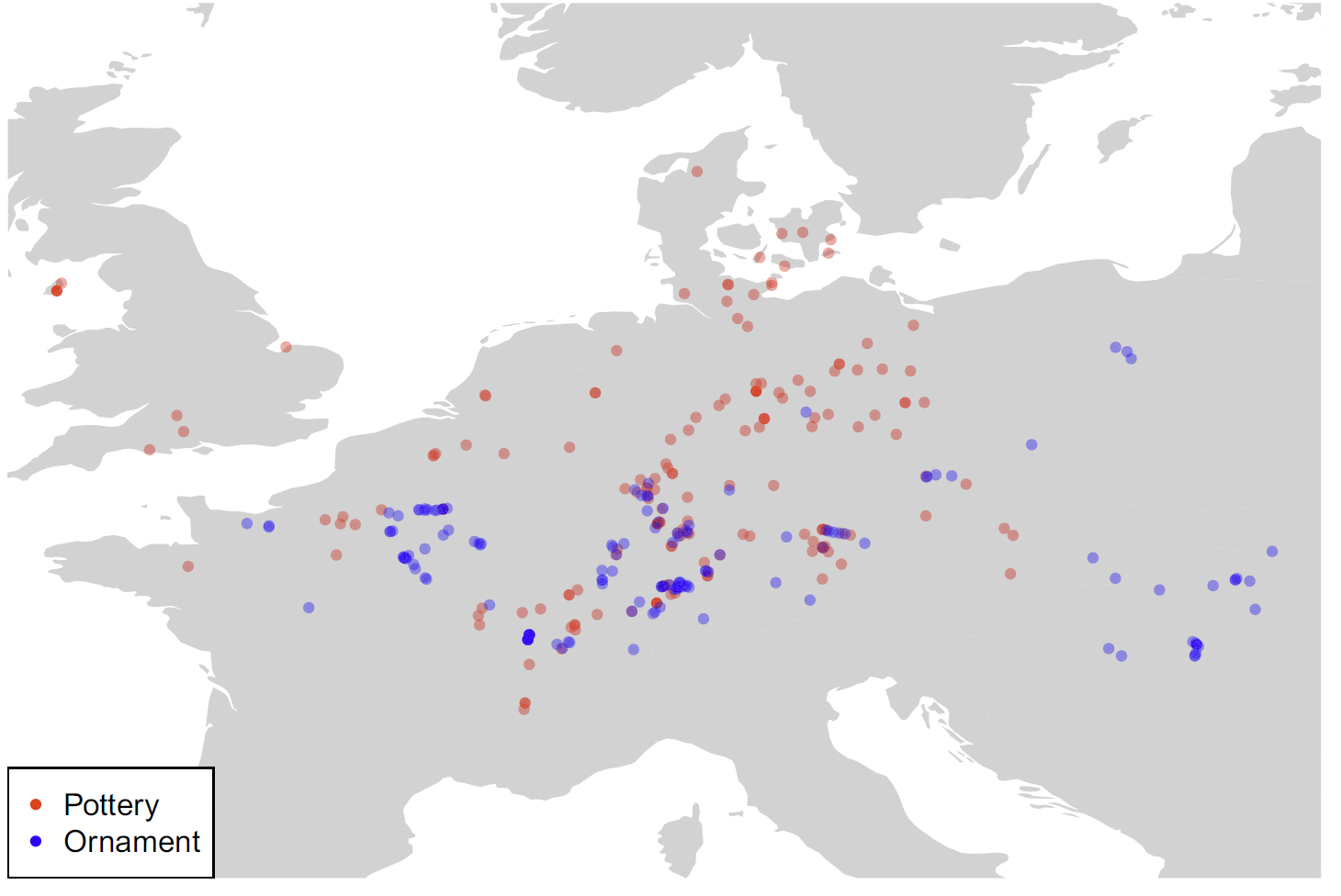

Recently there has been growing interest in characterising population structure in cultural data in the context of ongoing debates about the potential of cultural group selection as an evolutionary process. Here we use archaeological data for this purpose, which brings in a temporal as well as spatial dimension. We analyse two distinct material cultures (pottery and personal ornaments) from Neolithic Europe, in order to: a) determine whether archaeologically defined “cultures” exhibit marked discontinuities in space and time, supporting the existence of a population structure, or merely isolation-by-distance; and b) investigate the extent to which cultures can be conceived as structuring “cores” or as multiple and historically independent “packages”. Our results support the existence of a robust population structure comparable to previous studies on human culture, and show how the two material cultures exhibit profound differences in their spatial and temporal structuring, signalling different evolutionary trajectories.

Our results suggest distinct evolutionary histories in the spatial and temporal variation of personal ornament and pottery, with different rates of innovation, patterns of descent, and dynamics of diffusion. Ornament data do show statistically significant values of ΦST using pottery-defined population structures, but the magnitude is extremely small, and partial Mantel tests suggest that much of this pattern is explained by isolation by distance. These results are in line with a model

of culture represented by independent “packages” of multiple coherent units rather than one characterised by a distinct and fairly isolated “core” surrounded by a “periphery” of elements prone to crosscultural transmission. The alternative hypothesis is that one element was part of the “core” tradition, whilst the other was peripheral. This scenario is however less likely given that both elements are generally regarded as expression of local lines of transmission and/or signalling.The robust support for a population structure in the pottery data shows that some degree of homophily must have biased the transmission process, but this bias was confined within the single “package”, rather than affecting other aspects of the material culture. In other words similarity (or dissimilarity) of pottery style was not influencing the transmission process of personal ornaments and vice-versa. If this was the case, we should have observed a stronger agreement between in the spatio-temporal distribution of the two datasets, a pattern we failed to observe. Personal ornaments are often seen as group-identity markers, but the fact that our study appears to indicate a stronger role for isolation by distance in accounting for variation in ornaments suggests that this assumption may not be valid, or alternatively that these groups cross-cut the archaeological cultures traditionally recognised. Thus,while our study has provided strong evidence of population structure affecting patterns of cultural interaction, in this case at least the distinct patterns observed point to a modular, ‘package’ model. It has also shown that we can identify population structuring from the evidence of the archaeological record without continuing to attempt the fruitless task of correlating its patterns with past ethnolinguistic units.

Europe

A situation more interesting than Neolithic Europe for those following this blog will probably be the one on West Europe during the Bell Beaker expansion.

Regarding Iberia, I have already talked about the possibilities of “resurgence” after the arrival of Bell Beaker migrants, in this blog and in the Indo-European demic diffusion model.

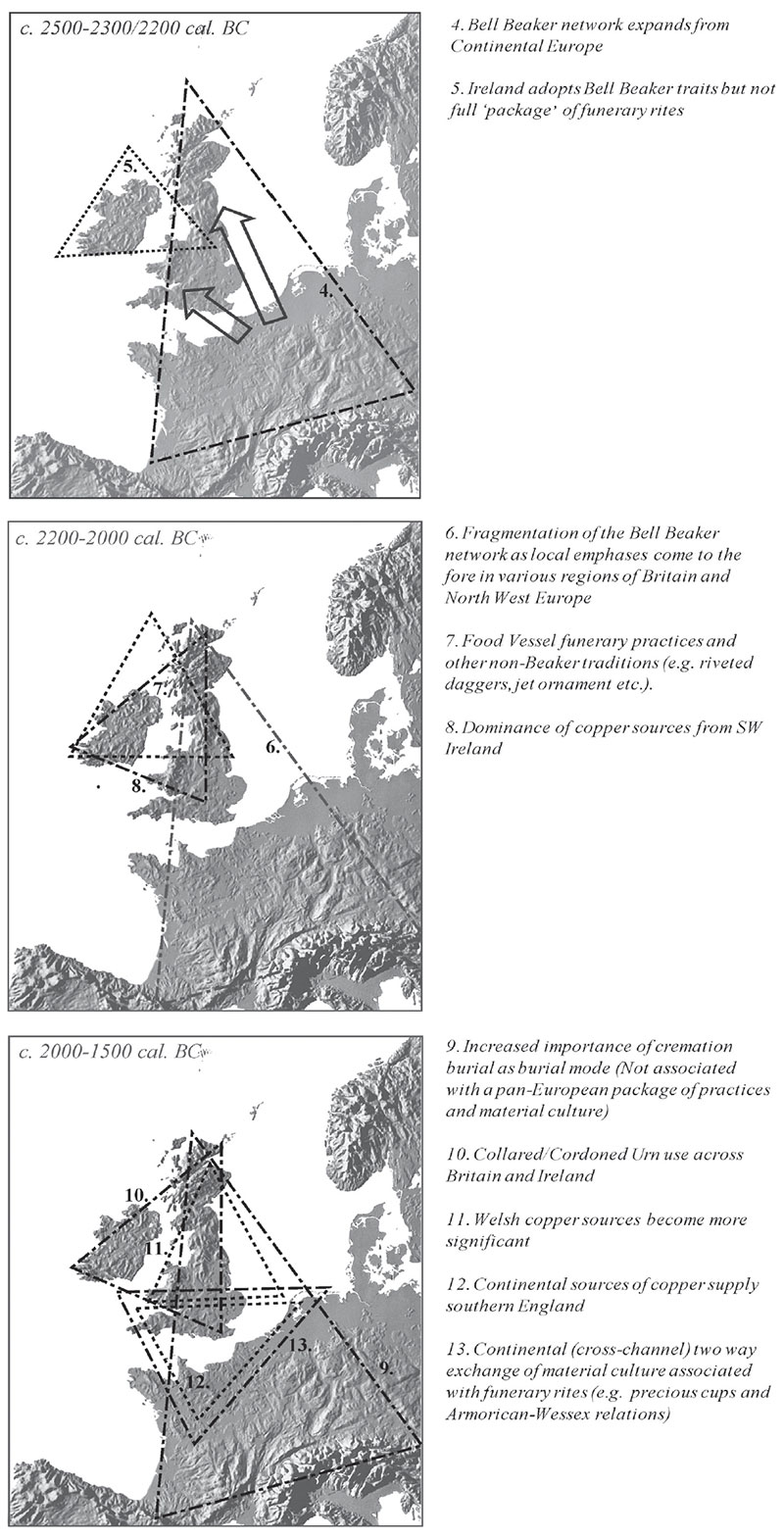

About the British Isles, you can read e.g. the stepped and different cultural changes that happened after the arrival of East Bell Beakers in What was and what would never be: changing patterns of interaction and archaeological visibility across north-west Europe from 2,500 to 1,500 cal BC, by Wilkin, N., Vander Linden, M. 2015. In : Anderson-Whymark, H., Garrow, D., Sturt, F. (eds)Continental connections. Exploring cross -Channel relationships from the Mesolithic to the Iron Age. Oxford: Oxbow: 99-121.

This logical description different cultural changes brings up a question obvious to many, and can be summed up by “does the arrival of (North-West Indo-European-speaking) East Bell Beakers mean the end of non-Indo-European cultures in Western and Northern Europe?” The answer is obviously – as in the rest of Europe – quite simply No. Many non-Indo-European groups must have survived the initial expansion of East Bell Beakers in many regions, as the pre-Roman situation (already quite simplified after the expansion of Celtic and Germanic) testifies.

“Resurgence” of local groups as seen in genomic data is the most direct connection with survival of previous non-IE cultures (and thus languages), but obviously not the only mechanism of language survival, since we can see founder effects – such as those seen in modern Basque speakers (mainly of R1b subclades), and in Ugro-Finnic speakers in north-east Europe (mainly of N subclades).

Steppe folk

I am recently stumbling more and more often upon the concept of ‘Steppe people‘ by amateur geneticists, whether in Anthrogenica, in blogs and blog comments, or even in research papers, where people used to talk about ‘Yamnaya people’ or ‘Yamnaya folk’. As I said, I expected this since I questioned the concept of the ‘Yamnaya ancestral component‘, so I feel vindicated by this change.

However, whereas most will be using these names simply following the redeeming term “steppe admixture”, and thus refer to a Neolithic steppe population that shared a common admixture component (probably ca. 5000 BC), some will obviously go further and identify this component with Proto-Indo-European (like that, in general terms), since it is the logical sequence for those who consider the term “Indo-Europeans” as an umbrella for a certain ethnic proportion and a link with modern populations in stupid autochthonous continuity theories, where prehistoric language and culture are irrelevant.

NOTE. Evidently, those who supported quite strongly the fact that R1a-M417 subclades associated with Corded Ware migrants (i.e. mainly R1a-Z645) stemmed directly from Yamna migrants are shifting terminology to “steppe people” in light of recent data, so that they can support an older steppe community in the likely case that no R1a is found in Yamna, while keeping open the possibility to revert to a more direct support of the Yamna -> Corded Ware model in case just one R1a sample is found… So no anthropological model at all here, just a personal desire to be fullfilled in any possible way.

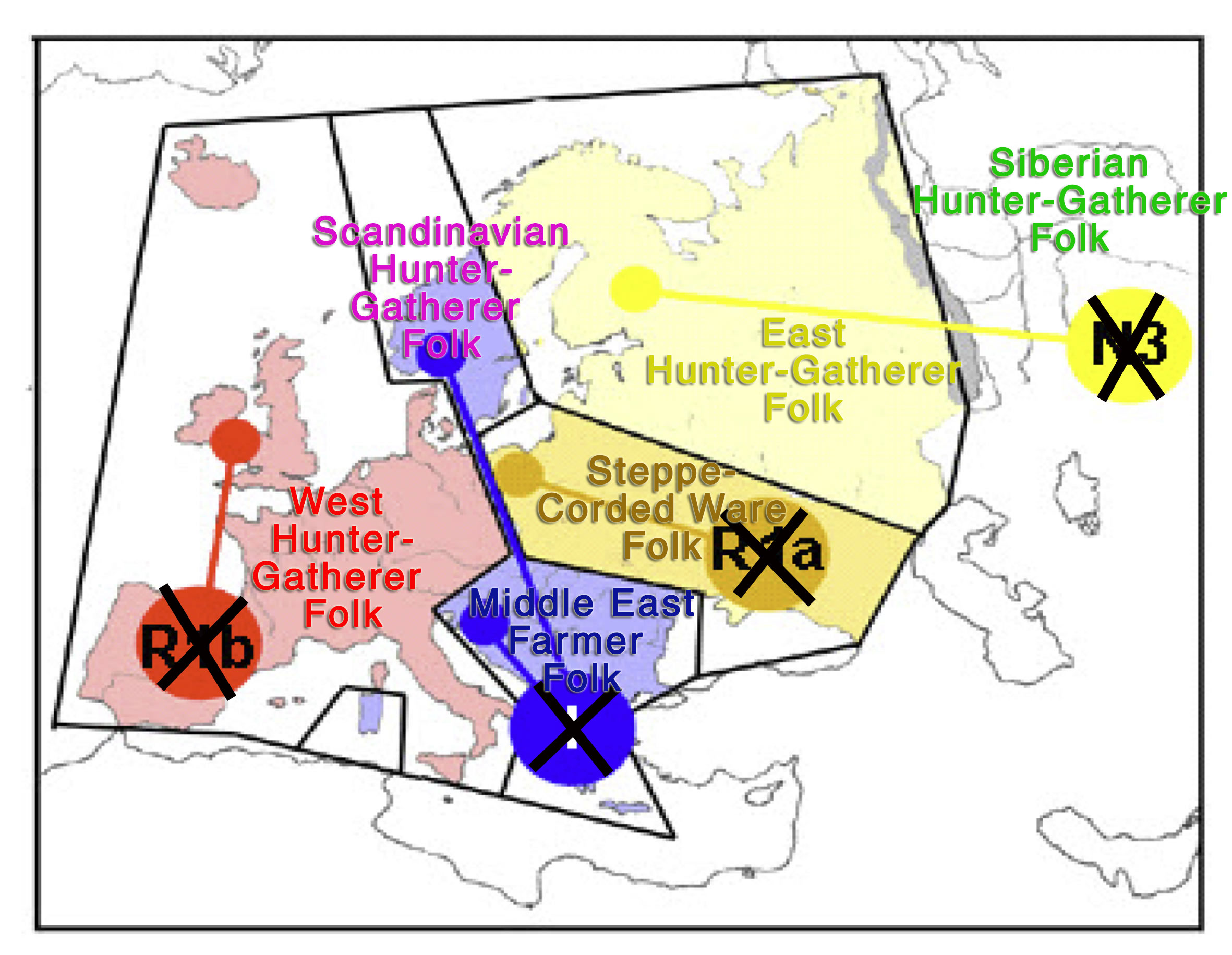

Those thinking naively about an imaginary ‘Steppe folk’, living in loosely connected steppe cultures, speaking a mixed ‘Steppe language’, may well keep inventing potentially popular peoples and languages based on admixture, such as West Hunter-Gatherer folk (Vasconic?), East Hunter-Gatherer folk (Uralic? – or maybe today they can invent a Siberian folk bringing Finno-Ugric after 500 BC), Caucasus Hunter-Gatherer folk (??), etc. So welcome back to the 1930s!… Or was it the 2000s?

Some people like to talk about how “Science” wins against Academia, especially when they try to defend this pseudo-subfield they are inventing and venerating on the go to characterize ancient populations, where new genomic methods are king, and the other fields involved are just noise they easily use or dismiss to support their own desires and preconceptions.

NOTE. I felt like many fans of Genomics are very well represented in this recent article at ArXiv: “23andMe confirms: I’m super white” — Analyzing Twitter Discourse On Genetic Testing

Too bad for them. The misuse of this new field might be popular today among certain amateur geneticists, but it will not stand the test of time, similar to how the initial hype around radiocarbon analysis (for Archaeology) or glottochronology (for Linguistics) eventually faded, and they became just another tool among traditional methods. In Science, time puts everything where it belongs.

Whether you like it or not, Indo-European (and Uralic) questions will be solved – as they have been for a long time now, there is nothing new under the sun – with Historical Linguistics first, then Prehistoric Archaeology, then Anthropology (models of migration, cultural diffusion, founder effects, etc.), and only then Genomics, which may (or may not) help solve certain controversial aspects, by supporting one or other anthropological model. Period.

See also:

- The Indo-European demic diffusion model, and the “R1b – Indo-European” association

- Science and Archaeology (Humanities): collaboration or confrontation?

- Massive Migrations? The Impact of Recent aDNA Studies on our View of Third Millennium Europe

- The new “Indo-European Corded Ware Theory” of David Anthony

- Bell Beaker/early Late Neolithic (NOT Corded Ware/Battle Axe) identified as forming the Pre-Germanic community in Scandinavia

- The renewed ‘Kurgan model’ of Kristian Kristiansen and the Danish school: “The Indo-European Corded Ware Theory”

- Correlation does not mean causation: the damage of the ‘Yamnaya ancestral component’, and the ‘Future America’ hypothesis

- Something is very wrong with models based on the so-called ‘Yamnaya admixture’ – and archaeologists are catching up (II)

- New Ukraine Eneolithic sample from late Sredni Stog, near homeland of the Corded Ware culture

- Germanic–Balto-Slavic and Satem (‘Indo-Slavonic’) dialect revisionism by amateur geneticists, or why R1a lineages *must* have spoken Proto-Indo-European