Henny Piezonka recently uploaded an old chapter, Die frühe Keramik Eurasiens: Aktuelle Forschungsfragen und methodische Ansätze, in Multidisciplinary approach to archaeology: Recent achievements and prospects. Proceedings of the International Symposium “Multidisciplinary approach to archaeology: Recent achievements and prospects”, June 22-26, 2015, Novosibirsk, Eds. V. I. Molodin, S. Hansen.

Abstract (in German):

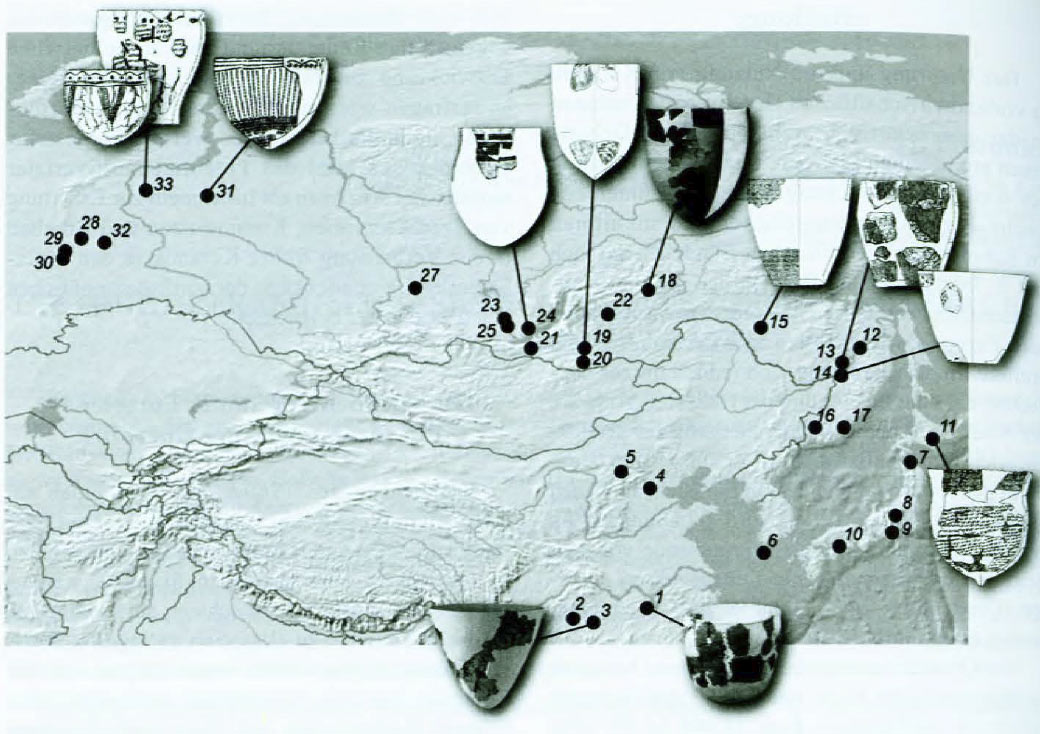

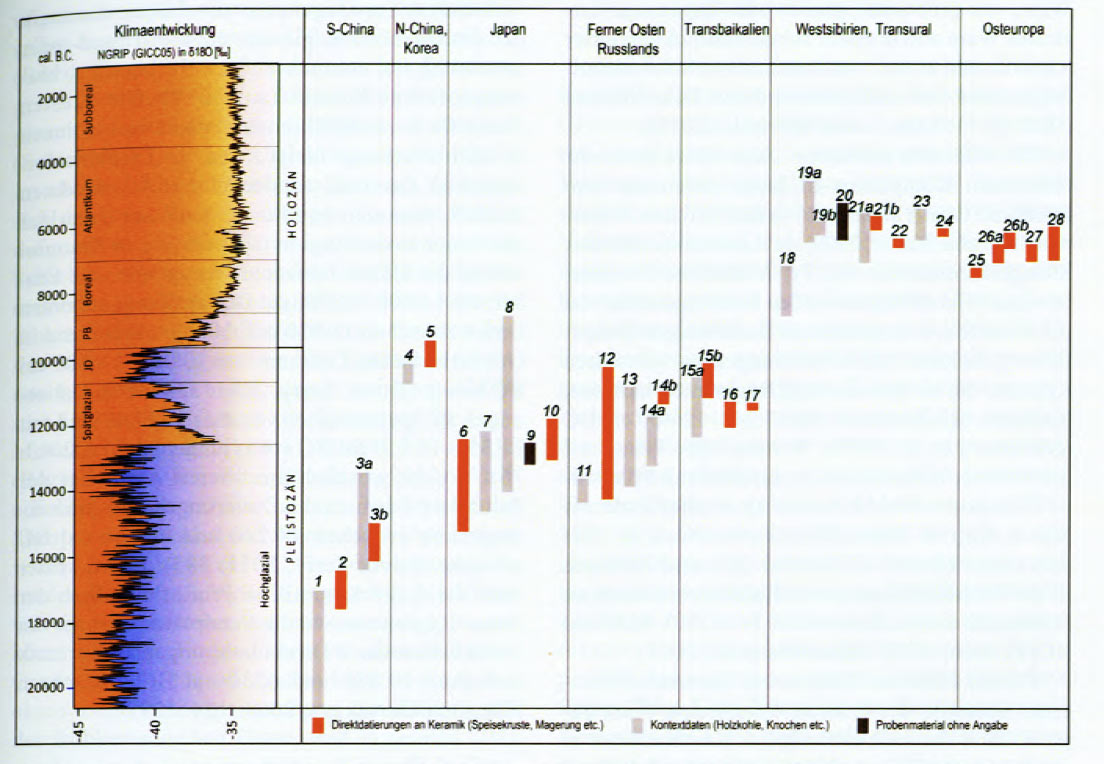

Die älteste bisher bekannte Gefäßkeramik der Welt wurde in Südostchina von spätglazialen Jäger-Sammlern wahrscheinlich schon um 18.000 cal BC hergestellt. In den folgenden Jahrtausenden verbreitete sich die neue Technik bei Wildbeutergemeinschaften in der russischen Amur-Region, in Japan, Korea und Transbaikalien bekannt, bevor sie im frühen und mittleren Holozän das Uralgebiet und Ost- und Nordeuropa erreichte. Entgegen verbreiteter Forschungsmeinungen zur Keramikgeschichte, die frühe Gefaßkeramik als Bestandteil des „neolithischen Bündes” der frühen Bauernkulturen sehen, stellt die eurasische Jäger-Sammler-Keramiktradition eine Innovation dar, die sich offenbar völlig unabhängig von anderen neolithischen Kulturerscheinungen wie Ackerbau, Viehzucht und sesshafre Lebensweise entwickelt hat Im vorliegenden Beitrag wird die chronologische Abfolge des ersten Auftretens von Tongefäßen in nordeurasischen Jäger-Sammler-Gemeinschaften anahnd von 14C-Datierungen Pazifik bis ins Baltikum nachvollzogen. Gleichzeitig werden vielversprechende methodische Ansätze vorgestellet, die derzeit ein Rolle bei der Erforschung dieses viel diskutierten Themas spielen.

If you have followed the updates to the Indo-European demic diffusion model, my proposal of a potential late arrival of haplogroup R1a-M417 during the Mesolithic did not change by the potential earlier arrival of EHG ancestry and haplogroup R1a in the North Pontic steppe, after the findings in Mathieson et al. (2017).

That is so because of the anthropological models of migration – or, lacking them, archaeological models of cultural expansion – that we have to date.

If I had followed a simplistic autochthonous continuity view, I would have thought that R1a-M417 was autochthonous to Eastern Europe, because an older subclade is found in the North Pontic steppe during the Mesolithic, akin to how some people want to believe that R1b-M269 shows autochthonous continuity in or around Central Europe, because of the Villabruna sample and later R1b-L23 subclades found there.

However, it is difficult to assert today that the population movement involving a community of mostly haplogroup R1a-M417 happened from west to east:

- If you follow Piezonka’s work, who did her Ph.D. dissertation in Eastern European Mesolithic (you can buy a more readable version), and has dedicated a great amount of time and effort to the research of cultural connections between Eastern Europe and Eurasia during the Mesolithic;

- taking into account the potential migration waves behind the increase in EHG ancestry in Eastern Europe in these periods, and this ancestral component’s speculative connection with ANE ancestry;

- and if we accept the TMRCA of R1a-M417 based on modern samples, dated ca. 6500 BC, and the appearance of the first samples at a similar time in Eastern Europe and in Baikalic cultures.

NOTE. More and more findings of Eastern Europe are showing how the sample of haplogroup N1c found in Eastern Europe and dated ca. 2500 BC is probably wrong, either in its haplogroup or in the radiocarbon date: after all, the lab has published just one study. The study of Baikalic samples, on the other hand, seems to have been corroborated by a more recent study.

Another interesting sample is that of Afontova Gora, whose community may have actually been mostly of haplogroup R1a (based on its position in PCA and relation to ANE ancestry), and thus the regional distribution of this haplogroup could have been quite large in North Eurasia during the Palaeolithic-Mesolithic transition, although this is highly speculative, like the connection WHG:ANE for EHG.

It is obvious that we cannot know what happened during these millennia without more samples, and indeed I don’t see anything a priori wrong with having an origin of R1a-M417 (and thus some sort of continuity) in Eastern Europe during the Mesolithic and Neolithic; just as I don’t see any problem with the continuity of other European haplogroups. Or with their discontinuity, mind you. That would not change the Proto-Indo-European homeland, or the complexity of language and ethnicity in Eastern Europe in the millennia following the expansion of Late Indo-European.

It just amazes me again and again how otherwise serious and capable people are often blinded by the desire to have their direct paternal line (some ancestors among an infinite number of them, probably representing for them genetically much less than other ancestral lines) stem from the own region and have the same ethnolinguistic affiliation since time immemorial, instead of betting for sounder migration models supported by anthropological data…

Related:

- The concept of “Outlier” in Human Ancestry (III): Late Neolithic samples from the Baltic region and origins of the Corded Ware culture

- Genetic prehistory of the Baltic Sea region and Y-DNA: Corded Ware and R1a-Z645, Bronze Age and N1c

- More evidence on the recent arrival of haplogroup N and gradual replacement of R1a lineages in North-Eastern Europe

- New Ukraine Eneolithic sample from late Sredni Stog, near homeland of the Corded Ware culture

- Science and Archaeology (Humanities): collaboration or confrontation?

- Massive Migrations? The Impact of Recent aDNA Studies on our View of Third Millennium Europe

- Recent archaeological finds near Indo-European and Uralic homelands

- Germanic–Balto-Slavic and Satem (‘Indo-Slavonic’) dialect revisionism by amateur geneticists, or why R1a lineages *must* have spoken Proto-Indo-European