(Continued from the post Corded Ware culture origins: The Final Frontier).

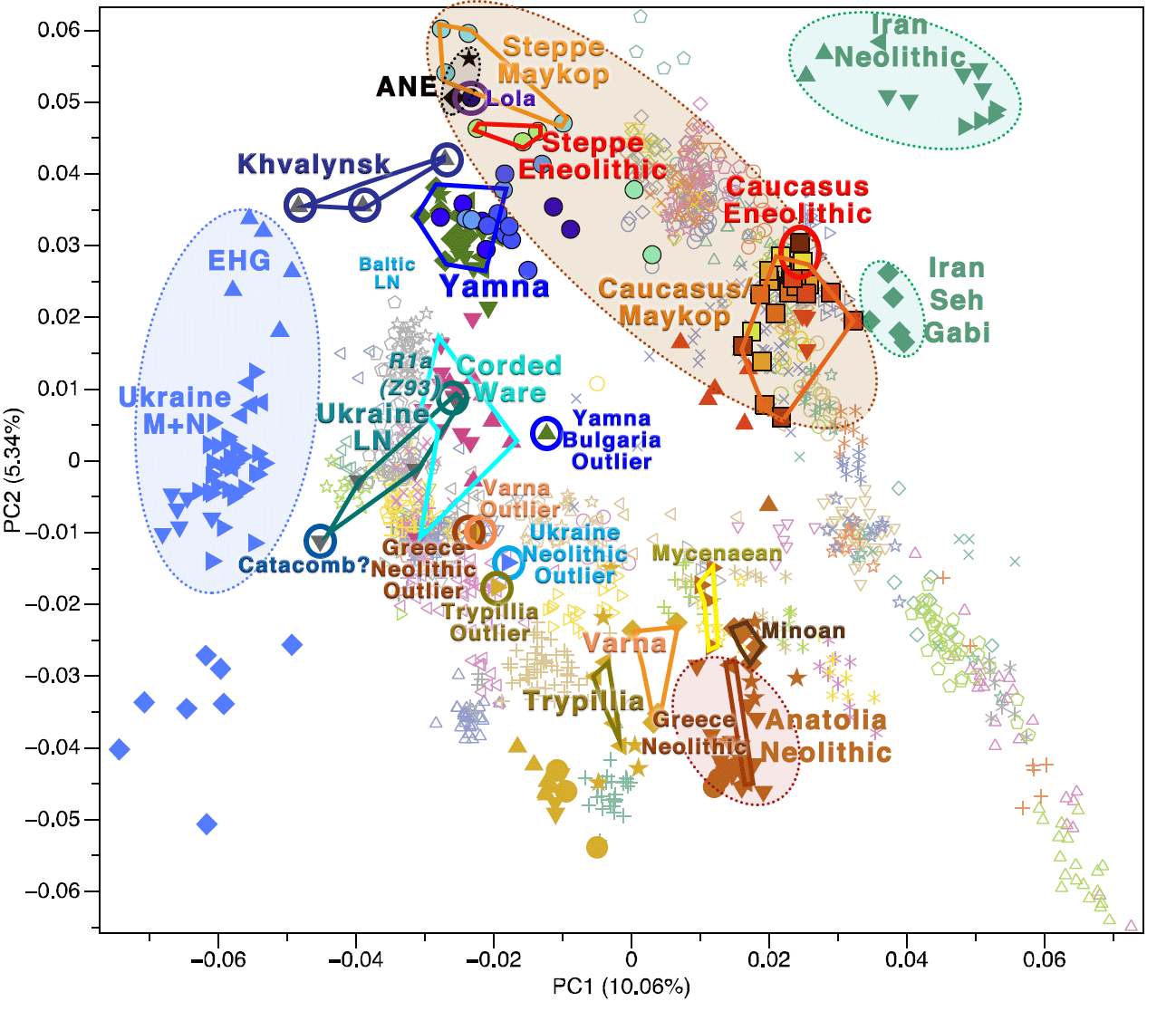

Looking at the PCA of Wang et al. (2018), I realized that Sredni Stog / Corded Ware peoples seem to lie somewhere between:

- the eastern steppe (i.e. Khvalynsk-Yamna); and

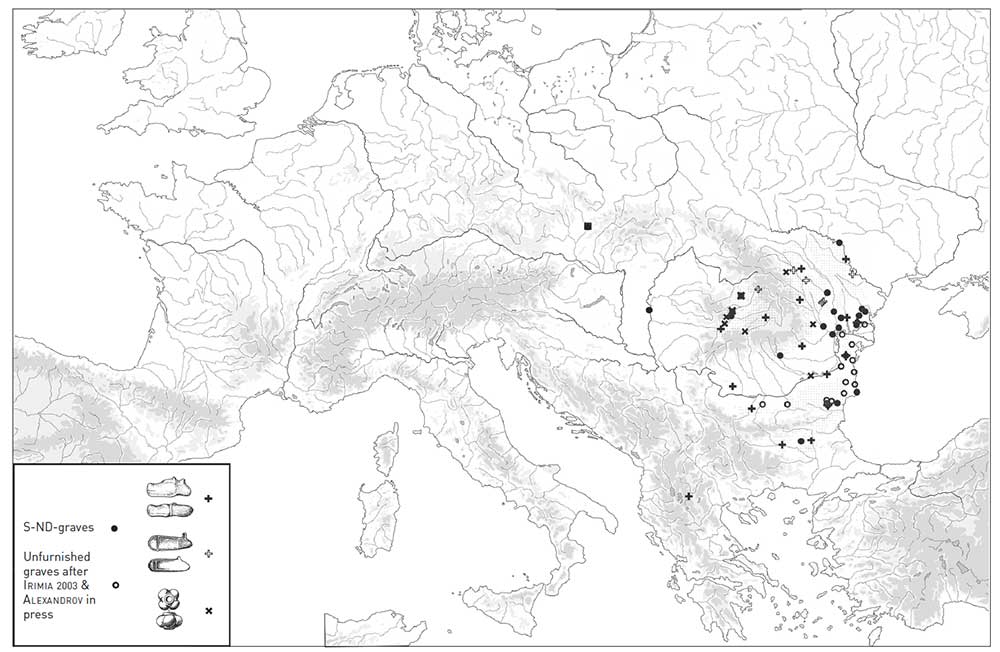

- Lower Danube and Balkan cultures affected by Anatolian- and steppe-related (i.e. Khvalynsk-Novodanilovka) migrations.

This multiethnic interaction of the western steppe fits therefore the complex archaeological description of events in the North Pontic, Lower Danube, and Dnieper-Dniester regions. Here are some interesting samples related to those long-lasting contacts:

1. I3719 (mtDNA H1, Y-DNA I2a2a) Ukraine Neolithic sample from Dereivka ca. 4949–4799 BC, described in Mathieson et al. (2018) as of “entirely northwestern-Anatolian-Neolithic-related ancestry”.

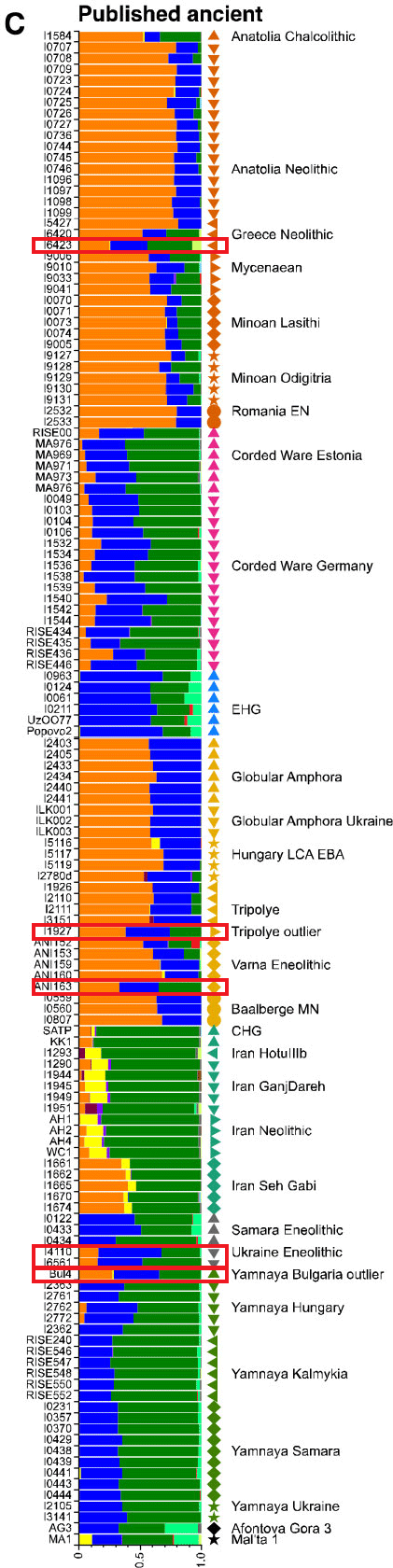

2. ANI163 from Varna I ca. 4711–4550 BC (mtDNA H7a1), and I2181 from Balkans Chalcolithic (Smyadovo, in Bulgaria) ca. 4500 BC (mtDNA HV15, Y-DNA R) show the first steppe ancestry in regions known to be affected by the expansion of Suvorovo chiefs.

3. The Yamna Bulgaria outlier (Y-DNA I2a2a1b1b), 3012-2900 calBCE, shows apparently an admixture with cultures of that region (but 1,500 years later).

Trypillia and Corded Ware

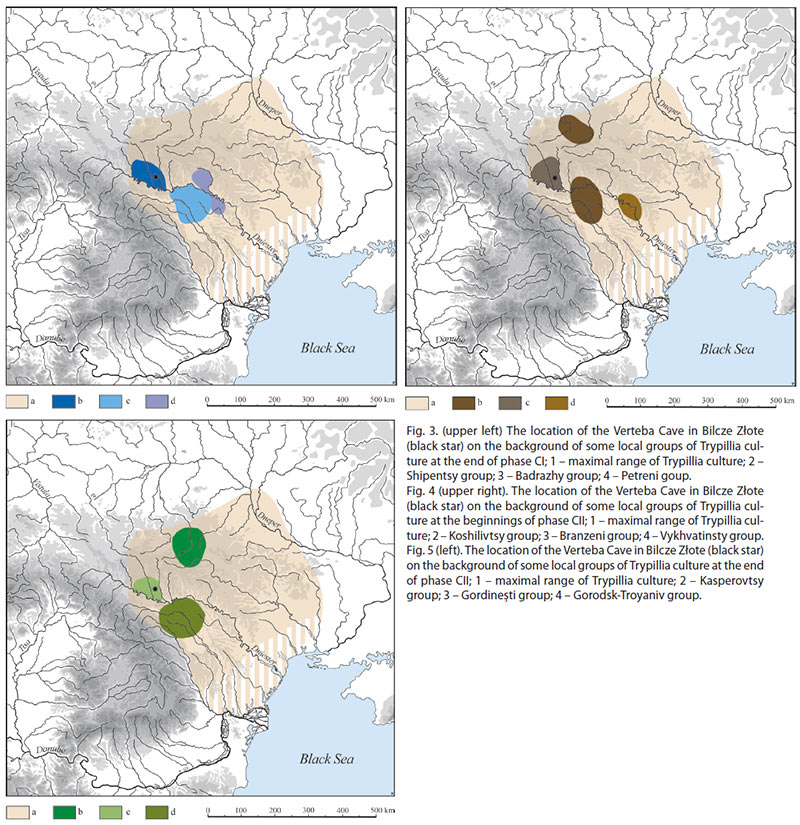

4. There is one ‘Trypillia outlier’ among five samples from the Verteba cave in Wang et al. (2018): I1927 (Y-DNA G2a2b2a1a1b1a1a1, mtDNA H1b), ca. 3619-2936 BC, a sample published previously in Nikitin et al. (2017) and Mathieson et al. (2017). We were very quick to dismiss Trypillia (three samples of haplogroup G2a, one sample E) and GAC as a source of Corded Ware admixture, but archaeology clearly shows important population movements at the end of the fourth millennium between late Trypillia groups, GAC, and post-Sredni Stog populations, and genetics is showing that in both cultures, too.

I am not a fan of the ‘lack of samples’ argument, but (similar to Old Hittite samples related to all Anatolian speakers) one site is not enough to describe a culture that spanned millennia and many different early and late groups. One among five Trypillian samples (from a single site), showing a late date (ca. 3228 BC) compared to the other samples (ca. 3700 BC), and quite close to the only three Ukraine Eneolithic samples we have may mean much more than what we may a priori think, i.e. some simplistic unidirectional punctual ‘intrusion’ of steppe ancestry, and instead hint at the known close contacts of late Trypillian groups and North Pontic cultures, including also the Caucasus.

NOTE. The big difference in PCA among GAC-like Hungary LCA – EBA samples (see above two star symbols close to Ukraine Neolithic outlier in the PCA, in contrast with the other three at the bottom) may also be significant, although we don’t have any data about their culture, sites, or the relationship between them.

Greece Neolithic outlier: Proto-Anatolians?

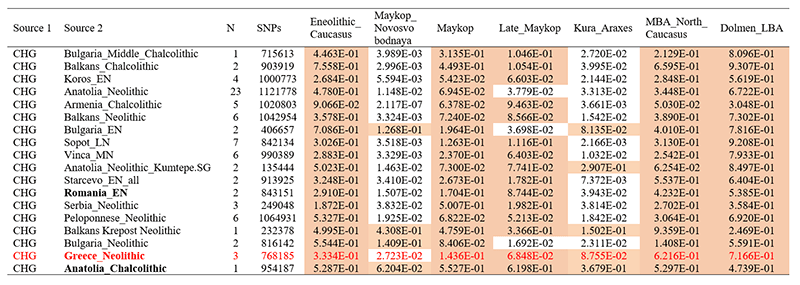

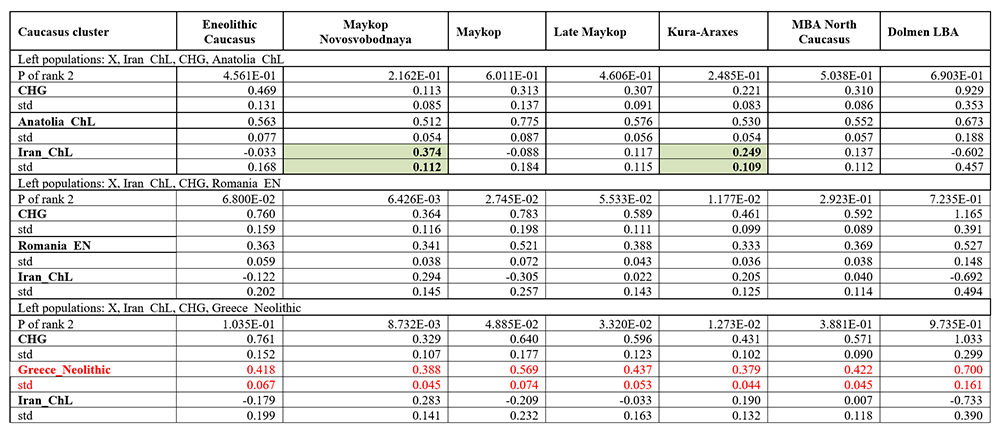

5. Especially interesting is I6423, one of the Greece Neolithic samples referred to in Wang et al. (2018), which is obviously an outlier among the three used in the paper. It does not seem to correspond to any of the ancient DNA samples published to date; it is not in Hofmanova et al. (2016), in Lazaridis et al. (2017), or in Mathieson et al. (2018).

Since the Neolithic in Greece could mean any period from ca. 6500 BC to ca. 3200 BC, I guess we are talking here about some migration related to the expansion of Khvalynsk-Novodanilovka chieftains after ca. 4500 BC, because it appears on the PCA precisely on the same spot as Varna and Smyadovo outliers, and its ADMIXTURE shows similar components…

So, this may be the smoking gun of Proto-Anatolian (or maybe early Common Anatolian) expansion with steppe migrants up to the border of Western Anatolia, and we may be able to get rid of those unfounded doubts about Anatolian origins once and for all…

NOTE. Also interesting seems another Greece Neolithic sample, I6420, in ADMIXTURE, although its position in the PCA (near Minoans and Mycenaeans) does not necessarily point to potential steppe influence, but rather to the extra ‘eastern (Caucasus/Iran-related) ancestry’ contribution found in Minoans and in Mycenaeans (and Anatolia Chalcolithic) compared to previous samples of the region. The third Greece Nelithic sample, I5427 (mtDNA K1a24), from Diros, Alepotrypa Cave, is dated 6005-5879 BC (mean 5892 BC), and appeared first in Mathieson et al. (2018).

If this Greece Neolithic sample is not related to Yamna migrations – and its use for statistical analysis of Caucasus samples from Wang et al. (2018) suggests that it is not – , it may have important consequences:

If it is located near the Western Anatolian coast – especially near Troy – there won’t be much to add about the potential site of entry of Common Anatolian languages into Anatolia… I have read some comments about how ‘impossible’ it was for steppe migrants and their language to ‘invade’ the more advanced cultures of Anatolia from the west, but it seems as ‘impossible’ as it was for Barbarians to invade the Roman Empire and impose their language as elites in certain regions. (And yes, we have at least one important weak political period among Middle Eastern cultures in the early 3rd millennium BC, similar to the period of the Fall of the Western Roman Empire).

If it is located somewhere more ‘central’ in the Greek Peninsula, then it could also be used to support the Anatolian nature of the controversial Pre-Greek (‘Pelasgian’) substrate. While we know that Greek (at least since Mycenaean) shows a strong Pre-Greek cultural and linguistic heritage (also reflected in its genetic continuity), the nature of that language is usually believed to be non-Indo-European, and Anatolian contacts are rather few and coincident with the Mycenaean period. I don’t think this sample can tell much about the Pre-Greek language, though, because – if it is really Neolithic, and comparing it with later Minoan and Mycenaean samples – it seems a clear outlier.

If it is, however, related to later Yamna migrations after ca. 3000 BC (and, like the ‘Ukraine Eneolithic’ sample that is likely from Catacomb, it is classified as Neolithic just because it cannot be attributed to precise Helladic periods), then we may be in front of the first obvious Yamna migrants in Greece. If that is the case (which I doubt), the sample wouldn’t be so informative for PIE dialectal expansions, because by now it is evident that we will find steppe ancestry and R1b-Z2103 subclades accompanying Yamna migrants in the southern Balkans, and probably well into Mycenaean Greece.

NOTE. Whatever the case, I am sure that for those fond of absurd autochthonous continuity theories, as well as for anti-steppe conspirationists, this sample will be just another good way of arguing for anything, ranging from a rejection of the Middle PIE – Late PIE division, to a support for some mythic ancient autochtonous Proto-Graeco-Anatolian group, or maybe some ancient Graeco–Indo-Slavonic split, or whatever new dialectal stage one can invent to support the own genealogical fantasies…

So, if it actually is a Neolithic sample, let’s hope that it shows a clear R1b-M269 (xL23 or early L23) subclade distinct from those (likely Z2103) expanded later with Late PIE-speaking Yamna (and probably to be found among Mycenaeans), so that there can be no more place for ethnic fantasies.

EDIT (28 JUL 2018): Added information on Greece Neolithic and Trypillia samples

Related

- Corded Ware culture origins: The Final Frontier

- Sredni Stog, Proto-Corded Ware, and their “steppe admixture”

- Kurgan origins and expansion with Khvalynsk-Novodanilovka chieftains

- About Scepters, Horses, and War: on Khvalynsk migrants in the Caucasus and the Danube

- Steppe and Caucasus Eneolithic: the new keystones of the EHG-CHG-ANE ancestry in steppe groups

- The Caucasus a genetic and cultural barrier; Yamna dominated by R1b-M269; Yamna settlers in Hungary cluster with Yamna

- The concept of “Outlier” in Human Ancestry (III): Late Neolithic samples from the Baltic region and origins of the Corded Ware culture

- Consequences of Damgaard et al. 2018 (II): The late Khvalynsk migration waves with R1b-L23 lineages

- On the potential origin of Caucasus hunter-gatherer ancestry in Eneolithic steppe cultures

- Eneolithic Ukraine cultures of the North Pontic steppe and southern steppe-forest, on the Left Bank of the Dnieper

- North Pontic steppe Eneolithic cultures, and an alternative Indo-Slavonic model

- New Ukraine Eneolithic sample from late Sredni Stog, near homeland of the Corded Ware culture

- The renewed ‘Kurgan model’ of Kristian Kristiansen and the Danish school: “The Indo-European Corded Ware Theory”