A recent comment on the hypothetical Central European origin of PIE helped me remember that, when news appeared that R1b-L51 had been found in Khvalynsk ca. 4250-4000 BC, I began to think about alternative scenarios for the expansion of this haplogroup, with one of them including Central Europe.

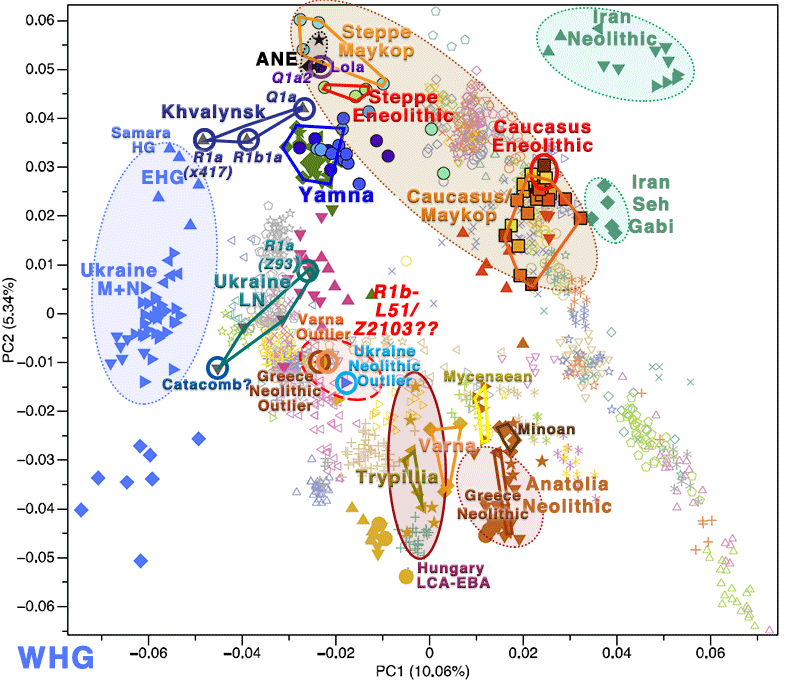

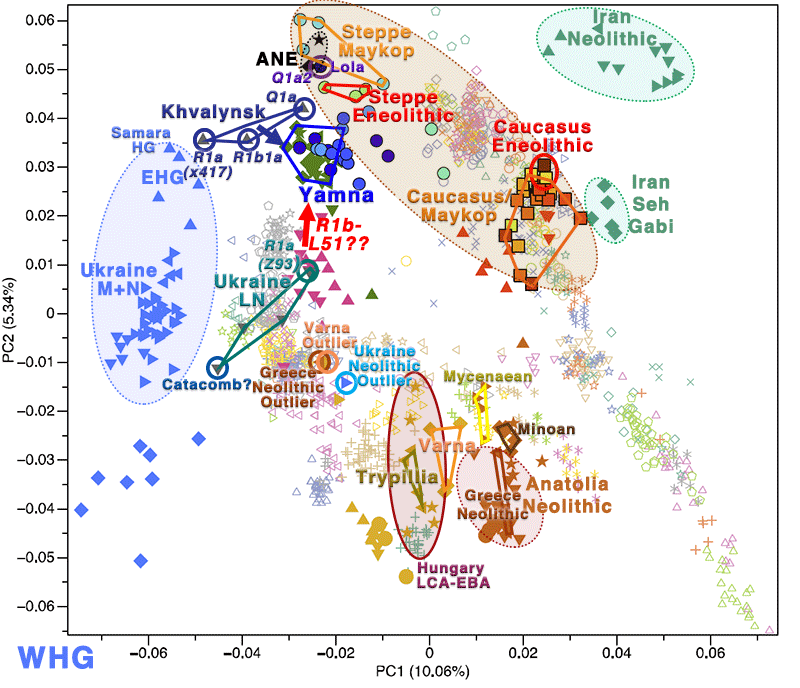

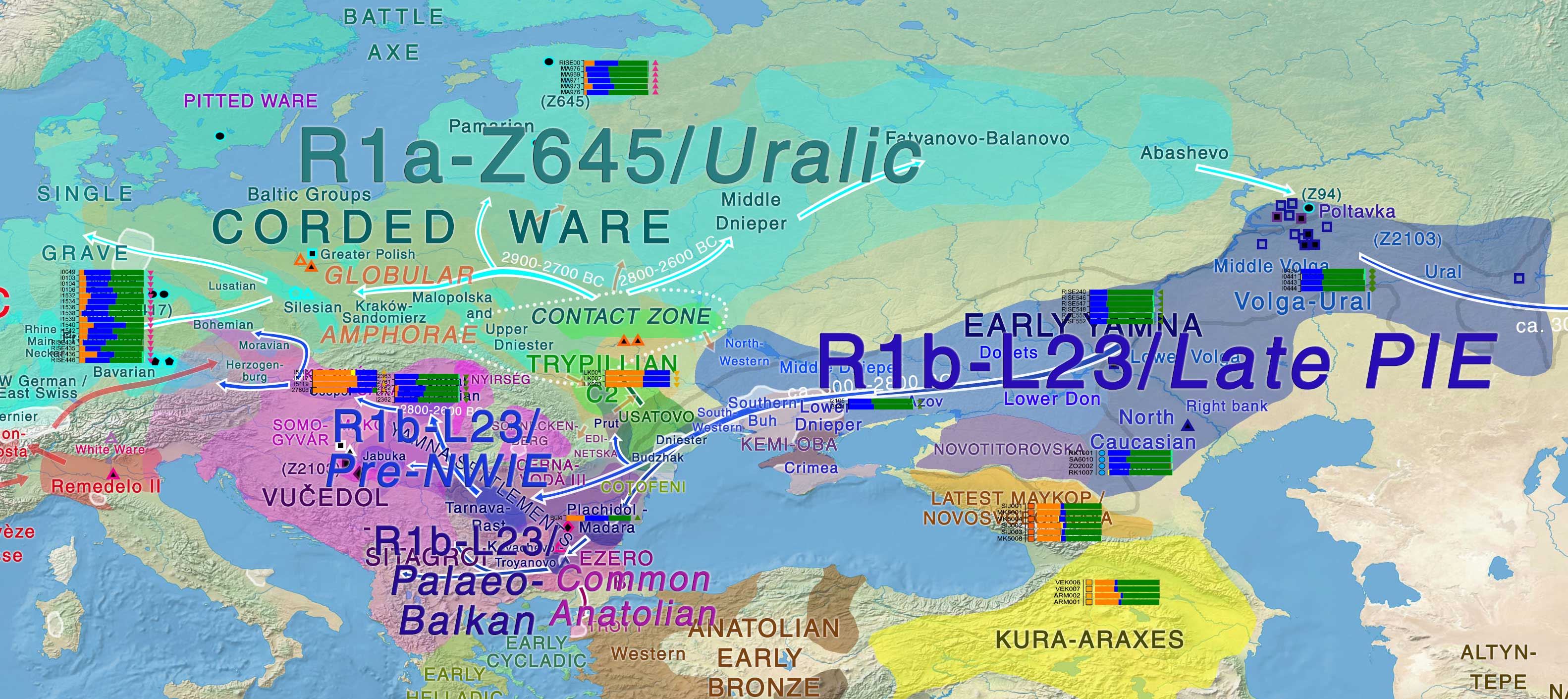

Because, if YFull‘s (and Iain McDonald‘s) estimation of the split of R1b-L23 in L51 and Z2103 (ca. 4100 BC, TMRCA ca. 3700 BC) was wrong, by as much as the R1a-Z645 estimates proved wrong, and both subclades were older than expected, then maybe R1b-L51 was not part of the Yamna expansion, but rather part of an earlier expansion with Suvorovo-Novodanilovka into central Europe.

That is, R1b-L51 and R1b-Z2103 would have expanded wih Khvalynsk-Novodanilovka migrants, and they would have either disappeared among local populations, or settled and expanded with successful lineages in certain regions. I think this may give rise to two potential models.

A hidden group in the European east-central steppes?

Here is what Heyd (2011), for example, has to say about the effect of the Khvalynsk-Novodanilovka expansion in the 4th millennium BC, with the first Kurgan wave that shuttered the social, economic, and cultural foundations of south-eastern Europe (before the expansion of west Yamna migrants in the region):

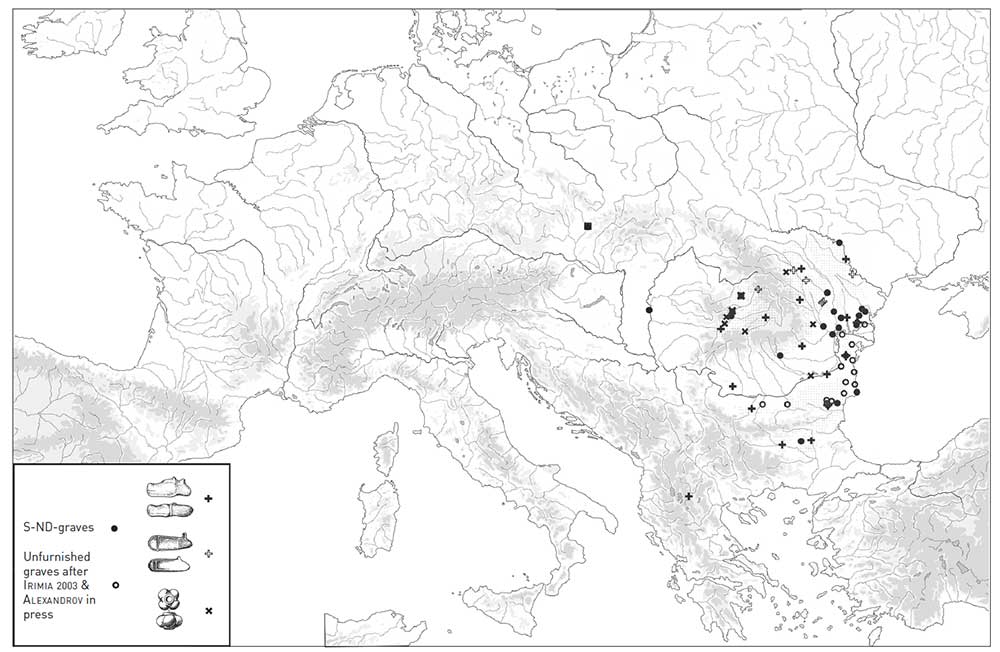

As the Boleraz and Baden tumuli cases in Serbia and Hungary demonstrate, there are earlier, 4th millennium cal. B.C. round tumuli in the Carpathian basin. There are also earlier north-Pontic steppe populations who infiltrated similar environments west of the Black Sea prior to the rise of the Yamnaya culture. This situation can be traced back to the 2nd half of the 5th millennium cal. B.C. to a group of distinct burials, zoomorphic maceheads, long flint blades, triangular flint points, etc., summarized under the term Suvurovo-Novodanilovka (Govedarica 2004; Rassamakin 2004; Anthony 2007; Heyd forthcoming 2011). They also erected round personalized tumuli, though smaller in size and height, above inhumations of single individuals. Suvorovo and Casimcea are the key examples in the lower Danube region of Romania. In northeast Bulgaria, the primary grave of Polska Kosovo (ochre-stained supine extended body position: information communicated by S. Alexandrov) can also be seen as such, as should the Targovishte-“Gonova mogila” primary grave 1 in the Thracian plain with a burial arranged in a supine position with flexed legs, southeast-northwest orientated, and strewed with ochre (Kanchev 1991 , p. 56- 57; Ivanova Gaydarska 2007). In addition to the many copper and shell beads, the 17.4cm long obsidian blade is exceptional, which links this grave to the Csongrád-“Kettoshalom” grave in the south Hungarian plain (Ecsedy 1979). It also yielded an obsidian blade ( 13.2cm long) and copper, shell and limestone beads.

However, no traces of a tumulus have been recorded above the Kettoshalom tomb. Conventionally, it is dated to the Bodrogkeresztur-period in east Hungary, shortly after 4000 cal. B.C., which would correspond very well with the suggested Cernavodă I (or its less known cultural equivalent in the Thracian plain) attribution for the “Gonova mogila” grave, a cultural background to which the Csongrád grave should have also belonged. Bodrogkeresztur and Cernavodă I periods are not the only examples of 4th millennium cal. B.C. tumuli and burials displaying this steppe connection. Indeed we can find this early steppe impact throughout the 4th millennium cal. B.C. These include adscriptions to the Horodiștea II (Corlateni-Dealul Stadole, grave I: Burtanescu l 998, p. 37; Holbocai, grave 34: Coma 1998, p. 16); to Gordinești-Cernavodă 11 (Liești-Movila Arbănașu, grave 22: Brudiu 2000); to Gorodsk-Usatovo (Corlăteni Dealul Cetăţii, grave I: Comșa 1998, p. 17- 18, in Romania; Durankulak, grave 982: Vajsov 2002, in Bulgaria); and to Cernavodă III(Golyama Detelina, tum. 4: Leshtakov, Borisov 1995), and early (end of 4th millennium cal. B.C.) Ezero in Ovchartsi, primary grave (Kalchev 1994, p. 134-138) and Golyama Detelina, tum. 2 (Kanchev 1991) in Bulgaria. Also the Boleráz and Baden tumuli of Banjevac-Tolisavac and Mokrin in the south Carpathian basin account for this, since one should perhaps take into account primary grave 12 of the Sárrédtudavari-Orhalom tumulus in the Hungarian Alfold: a left-sided crouched juvenile ( 15- 17 y) individual in an oval, NW-SE orientated grave pit 14C dated to 3350-3100 cal. B.C. at 2 sigma (Dani, Ncpper 2006). Neither the burial custom (no ochre strewing or depositing a lump of ochre has been recorded), nor date account for its ascription to the Yamnaya!

All of these tumuli and burials demonstrate, though, that there is already a constant but perhaps low-level 4th millennium cal. B.C. steppe interaction, linking the regions of the north of the Black Sea with those of the west, and reaching deep into the Carpathian basin. This has to be acknowledged. even if these populations remain small, bounded to their steppe habitat with an economy adapted to this special environment, and are not always visible in the record. Indirect hints may help in seeing them, such as the frequent occurrence of horse bones, regarded as deriving from domesticated horses, in Hungarian Baden settlements (Bokonyi 1978; Benecke 1998), and in those of the south German Cham Culture (Matuschik 1999, p. 80-82) and the east German Bernburg Culture (Becker 1999; Benecke 1999). These occur, however, always in low numbers, perhaps not enough to maintain and regenerate a herd. Does this point us towards otherwise archaeologically hidden horsebreeders in the Carpathian basin, before the Yamnaya? In any case, I hope to make one case clear: these are by no means Yamnaya burials in the strict definition! Attribution to the Yamnaya in its strict definition applies.

Also, about the expansion of Yamna settlers along the steppes:

However, it should have been made clear by the distribution map of the Western Yamnaya that they were confining themselves solely to their own, well-known, steppe habitat and therefore not occupying, or pushing away and expelling, the locally settled farming societies. Also, living solely in the steppes requires another lifestyle, and quite different economic and social bases, most likely very different to the established farming societies. Although surely regarded as incoming strangers, they may therefore not have been seen as direct competitors. This argument can be further enforced when remembering that the lowlands and the steppes in the southeast of Europe had already been populated throughout the 4th millennium cal. B.C., as demonstrated above, by societies with a similar north-Pontic steppe origin and tradition, albeit in lower numbers. It is only for these groups that the Yamnaya may have become a threat, but their common origin and perhaps a similar economic/ social background with comparable lifestyles would surely have assisted to allow rapid assimilation. More important, though, is that farming societies in this region may therefore have been accustomed to dealing and interacting with different people and ethnic strangers for a long time. (…)

When assessing farming and steppe societies’ interaction from a general point of view, attitudes can diverge in three main directions:

- the violent one; with raids, fights, struggles, warfare, suppression and finally the superiority and exploitation of the one over the other;

- the peaceful one; with a continuous exchange of gifts, goods, work, information and genes in a balanced reciprocal system, leading eventually to the merging of the two societies and creation of a new identity;

- the neutral one; with the two societies ignoring each other for a long time.

What we see from trying to understand the record of the Yamnaya, based on their tumuli and burials, and the local and neighbouring contemporary societies, based on their settlements, hoards, and graves, is likely a mixture of all three scenarios, with the balance perhaps more towards exchange in a highly dynamic system with alterations over time. However, violence and raids cannot be ruled out; they would be difficult to see in the archaeological record; or only indirectly, such as the building of hill forts, particularly the defence-like chain of Vucedol hillforts along the south shore of the Danube on the Serbian/Croatian border zone (Tasic 1995a), and the retreat of people into them (Falkenstein 1998, p. 261-262), with other interpretations also possible. And finally, we are dealing here with very different local and neighbouring societies, as well as with more distant contemporary ones, looking, in reality, rather like a chequer board of societies and archaeological cultures (see Parzinger 1993 for the overview). These display different regional backgrounds and traditions leading to different social and settlement organizations, different economic bases and material cultures in the wide areas between Prut and Maritza rivers, and Black Sea and Tisza river. They surely found their individual way of responding to the incoming and settling Yamnaya people.

The best data we have about this potential non-Yamna origin of R1b-L51 – and thus in favour of its admixture in the Carpathian basin – lies in:

- The majority of R1a-Z2103 subclades found to date among Yamna samples.

- The presence of R1b-Z2103 in the Catacomb culture – in the Northern Caucasus and in Ukraine.

- The limited presence of (ancient and modern) R1b-L51 in eastern Europe and India, whose isolated finds are commonly (and simplistically) attributed to ‘late migrations’.

- The presence of R1b-L51 (xZ2103) in cultures related to the ‘Yamna package’, but supposedly not to Yamna settlers. So for example I7043, of haplogroup R1b-L151(xU106,xP312), ca. 2500-2200 BC from Szigetszentmiklós-Üdülősor, probably from the Bell Beaker (Csepel group), but maybe from the early Nagýrev culture.

- The expansion of its subclades apparently only from a single region, around the Carpathian basin, in contrast to R1b-Z2103.

- The already ‘diluted’ steppe admixture found in the earliest samples with respect to Yamna, which points to the appearance after the Yamna admixture with the local population.

- Ukrainian archaeologists (in contrast to their Russian colleagues) point to the relevance of North Pontic cultures like Kvitjana and Lower Mikhailovka in the development of Early Yamna in the west, and some eastern European researchers also believe in this similarity.

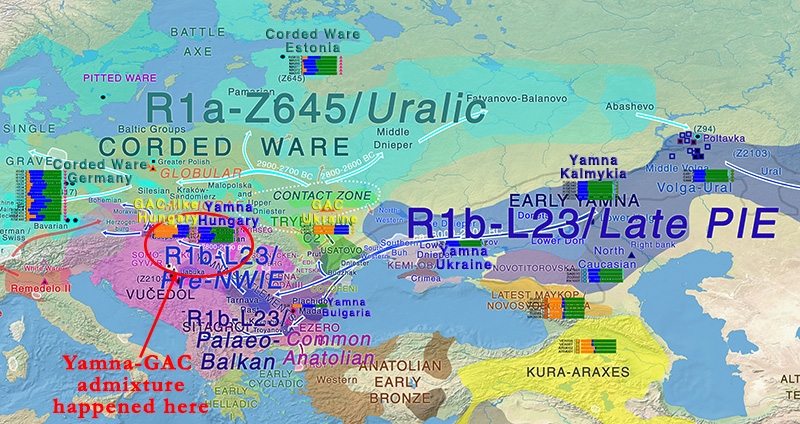

- If R1b-Z2103 and R1b-L51 had expanded with Suvorovo-Novodanilovka migrants to the west, and had admixed later as Hungary_LCA-LBA-like peoples with Yamna migrants during the long-term contacts with other ‘kurganized cultures’ ca. 2900-2500 BC in the Great Hungarian Plains, it could explain some peculiar linguistic traits of North-West Indo-European, and also why R1b-Z2103 appears in cultures associated with this earlier ‘steppe influence’ (i.e. not directly related to Yamna) such as Vučedol (with a R1b-Z2103 sample, see below). That could also explain the presence of R1b-L151(xP312, xU106) in similar Balkan cultures, possibly not directly related to Yamna.

A hidden group among north or west Pontic Eneolithic steppe cultures?

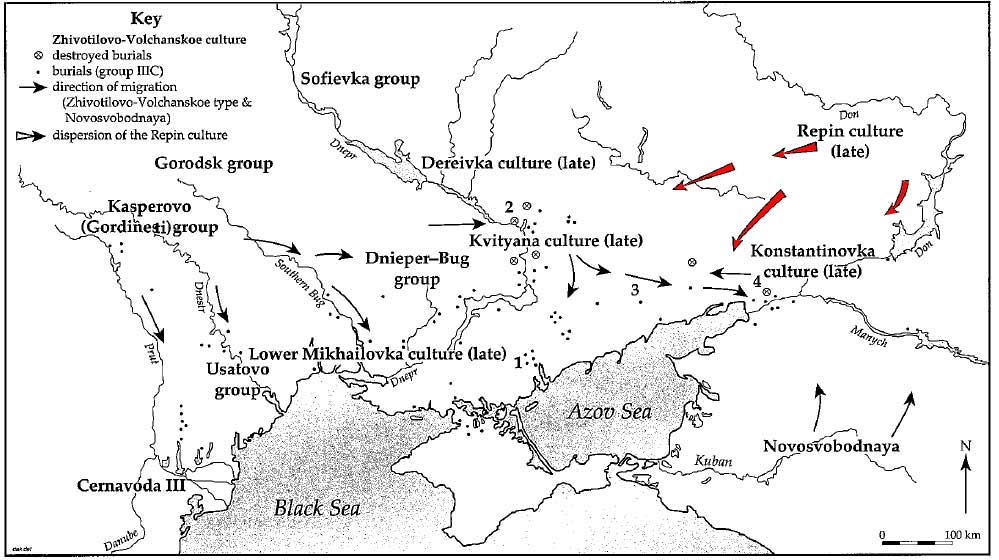

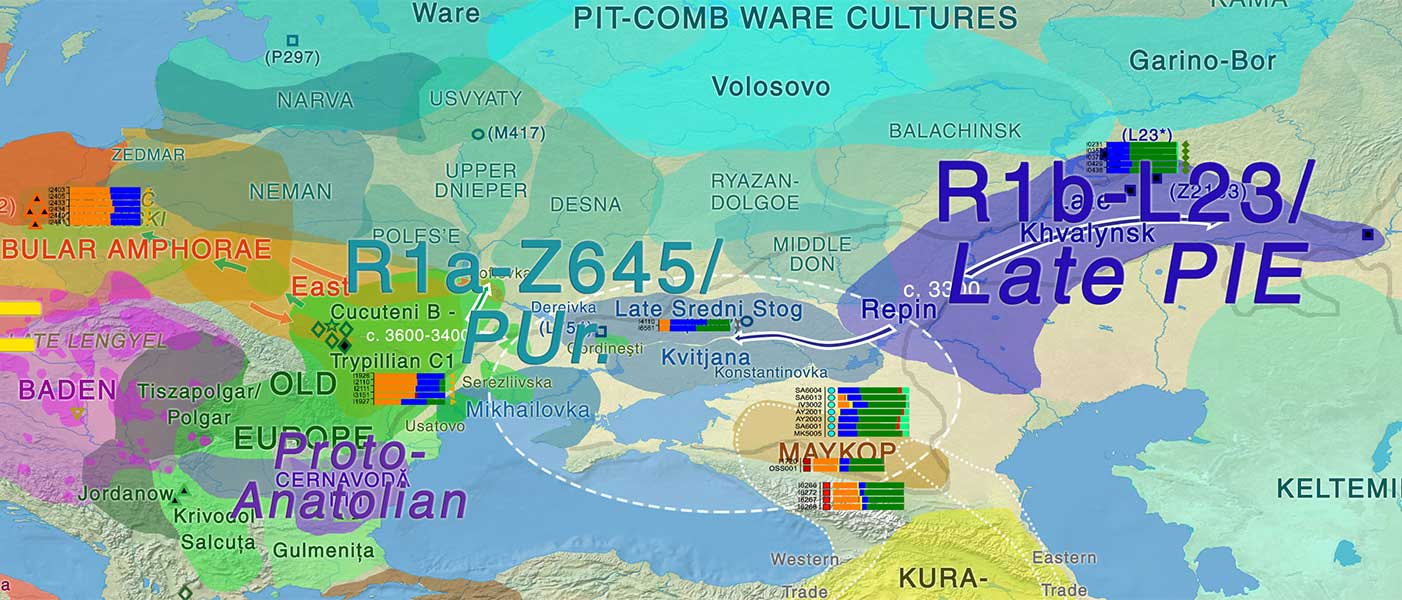

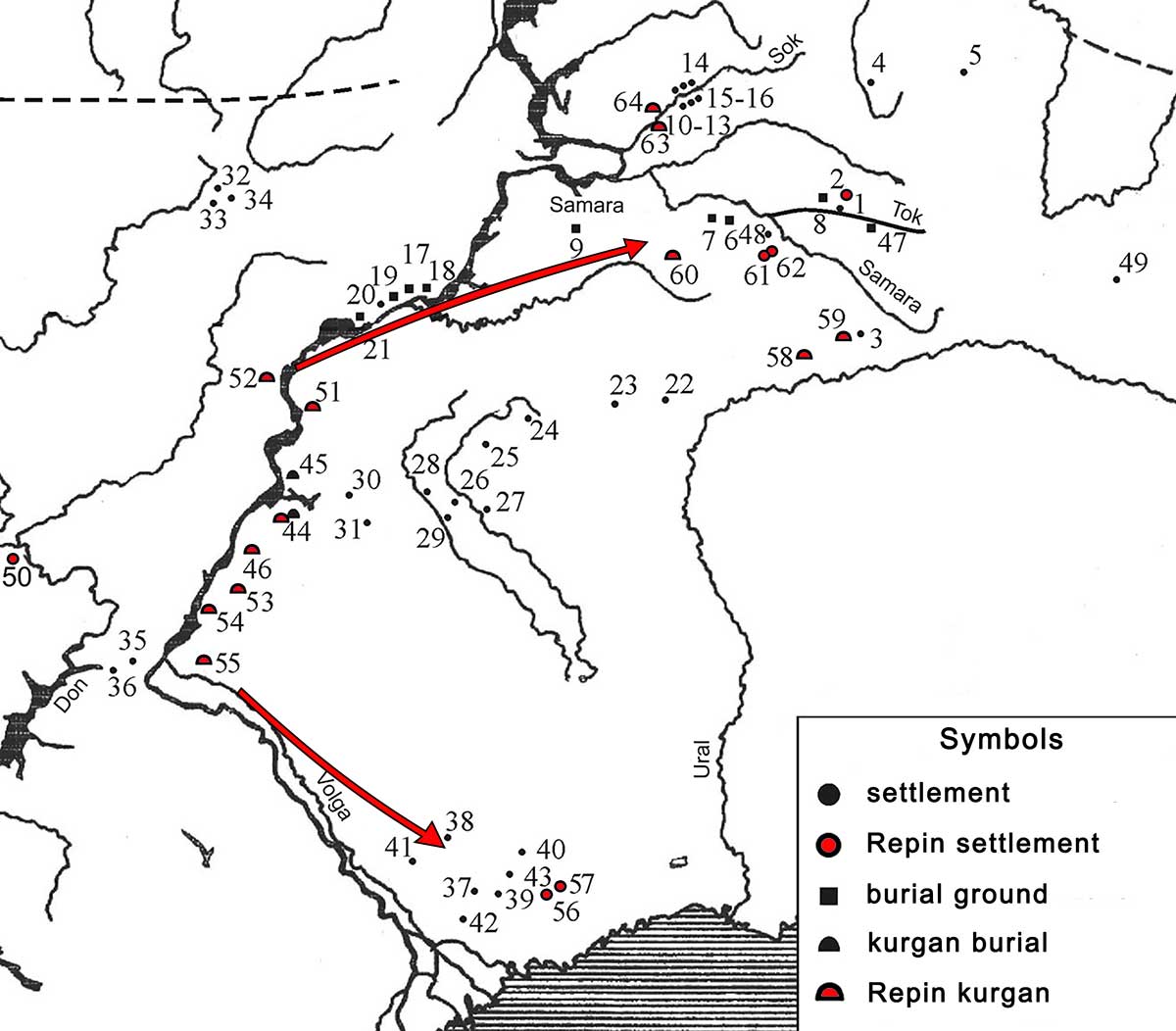

The expansion of Khvalynsk as Novodanilovka into the North Pontic area happened through the south across the steppe, near the coast, with the forest-steppe region working as a clear natural border for this culture of likely horse-riding chieftains, whose economy was probably based on some rudimentary form of mobile pastoralism.

Although archaeologists are divided as to the origin of each individual Middle Eneolithic group near the Black Sea after the end of the Khvalynsk-Novodanilovka period, it seems more or less clear that steppe cultures like Cernavodă, Lower Mikhailovka, or Kvitjana are closer (or “more archaic”) in their steppe features, which connects them to Volga–Ural and Northern Caucasus cultures, like Northern Caucasus, Repin or Khvalynsk.

On the other hand, forest-steppe cultures like Dereivka (including Alexandria) show innovative traits and contacts with para- or sub-Neolithic cultures to the north, like Comb-Pit Ware groups, apart from corded decoration influenced by Trypillian groups to the west, especially in their later (‘Proto-Corded Ware‘) stage after ca. 3500 BC.

If Ukrainian researchers like Rassamakin are right, Early Yamna expanded not only from Repin settlers, but also from local steppe cultures adopting Repin traits to develop an Early Yamna culture, similar to how eastern (Volga–Ural groups) seem to have synchronously adopted Early Yamna without massive affluence of Repin settlements.

Furthermore, local traits develop in southern groups, like anthropomorphic stelae (shared with Kemi-Oba, direct heir of Lower Mikhailovka), and rich burials featuring wagons. These traits are seen in west Yamna settlers.

Problems of this model include:

- On the North Pontic area – in contrast to the Volga–Ural region – , there was a clear “colonization” wave of Repin settlers, also supported by Ukrainian researchers, based on the number of new settlements and burials, and on the progressive retreat of Dereivka, Kvitjana, as well as (more recent) Maykop- and Trypillia-related groups from the North Pontic area ca. 3350/3300 BC. It seems unlikely that these expansionist, semi-nomadic, cattle-breeding, patrilineally-related steppe clans that were driving all native populations out of their territories suddenly decided, at some point during their spread into the North Pontic area ca. 3300-3100 BC, to join forces with some foreign male lineages from the area, and then continue their expansion to the west…

- Similar to the fate of R1b-P297 subclades in the Baltic after the expansion of Corded Ware migrants, previous haplogropus of the North Pontic region – such as R1a, R1b-V88, and I2 subclades basically disappeared from the ancient DNA record after the expansion of Khvalynsk-Novodanilovka, and then after the expansion of Yamna, as is clear from Yamna, Afanasevo, and Bell Beaker samples obtained to date. This, in combination with what we know about Y-chromosome bottlenecks in post-Neolithic expansions, leaves little space to think that a big enough territorial group with a majority of “native” haplogroups could survive later expansions (be it R1b-L51 or R1a-Z645).

- Supporting an expansion of the same male (and partly female) population, the Yamna admixture from east to west is quite homogeneous, with the only difference found in (non-significant) EEF-like proportion which becomes elevated in distant areas [apart from significant ‘southern’ contribution to certain outlier samples]. Based on the also homogeneous Y-DNA picture, the heterogeneity must come, in general, from the female exogamy practiced by expanding groups.

- There is a short period, spanning some centuries (approximately 3300-2700 BC), in which the North Pontic area – especially the forest-steppe territories to the west of the Dnieper, i.e. the Upper Dniester, Boh, and Prut-Siret areas – are a chaos of incoming and emigrating, expanding and shrinking groups of different cultures, such as late Trypillian groups, Maykop-related traits, TRB, GAC, (Proto-)Corded Ware, and Early Yamna settlements. No natural geographic frontier can be delimited between these groups, which probably interacted in different ways. Nevertheless, based on their cultural traits, admixture, and especially on their Y-DNA, it seems that they never incorporated foreign male lineages, beyond those they probably had during their initial expansion trends.

- The further expansionist waves of Early Yamna seen ca. 3100 BC, from the Danube Delta to the west, give an overall image of continuously expanding patrilineal clans of R1b-M269 subclades since the Khvalynsk-Novodanilovka migration, in different periodic steps, mostly from eastern Pontic-Caspian nuclei, usually overriding all encountered cultures and (especially male) populations, rather than showing long-term collaboration and interaction. Such interaction is seen only in exceptional cases, e.g. the long-term admixture between Abashevo and Poltavka, as seen in Proto-Indo-Iranian peoples and their language.

Consequences

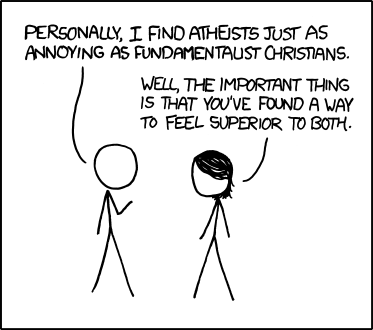

We are living right now an exemplary ego-, (ethno-)nationalism-, and/or supremacy-deflating moment, for some individuals of eastern and northern European descent who believed that R1a or ‘steppe ancestry proportions’ meant something special. The same can be said about those who had interiorized some social or ethnolinguistic meaning for the origin of R1b in western Europe, N1c in north-eastern Europe, as well as Greeks, Iranians, Armenians, or Mediterranean peoples in general of ‘Near Eastern’ ancestry or haplogroups, or peoples of Near Eastern origin and/or language.

These people had linked their haplogroups or ancestry with some fantasy continuity of ‘their’ ancestral populations to ‘their’ territories or languages (or both), and all are being proven wrong.

Apart from teaching such people a lesson about what simplistic views are useful for – whether it is based on ABO or RH group, white skin, blond hair, blue eyes, lactase persistence, or on the own ancestry or Y-DNA haplogroup -, it teaches the rest of us what can happen in the near future among western Europeans. Because, until recently, most western Europeans were comfortably settled thinking that our ancestors were some remnant population from an older, Palaeolithic or Mesolithic population, who acquired Indo-European languages by way of cultural diffusion in different periods, including only minor migrations.

Judging by what we can see now among some individuals of Northern and Eastern European descent, the only thing that can worsen the air of superiority among western Europeans is when they realize (within a few years, when all these stupid battles to control the narrative fade) that not only are they the cultural ‘heirs’ of the Graeco-Roman tradition that began with the Roman Empire, but that most of them are the direct patrilineal descendants of Khvalynsk, Yamna, Bell Beaker, and European Bronze Age peoples, and thus direct descendants of Middle PIE, Late PIE, and NWIE speakers.

The finding of R1b-L51 and R1b-Z2103 among expanding Suvorovo-Novodanilovka chieftains, with pockets of R1b-L51 remaining in steppe-like societies of the Balkans and the Carpathian Basin, would have beautifully complemented what we know about the East Yamna admixture with R1a-Z93 subclades (Uralic speakers) ca. 2600-2100 BC to form Proto-Indo-Iranian, and about the regional admixtures seen in the Balkans, e.g. in Proto-Greeks, with the prevalent J subclades of the region.

It would have meant an end to any modern culture or nation identifying themselves with the ‘true’ Late PIE and Yamna heirs, because these would be exclusively associated with the expansion of R1b-Z2103 subclades with late Repin, and later as the full-fledged Late PIE with Yamna settlers to south-east and central Europe, and to the southern Urals. The language would have had then obviously undergone different language changes in all these territories through long-lasting admixture with other populations. In that sense, it would have ended with the ideas of supremacy in western Europe before they even begin.

The most likely future

However limited the evidence, it seems that R1b-L51 expanded with Yamna, though, based on the estimates for the haplogroups involved, and on marginal hints at the variability of L23 subclades within Yamna and neighbouring populations. If R1b-L51 expanded with West Repin / Early Yamna settlers, this is why they have not yet been found among Yamna samples:

- The subclade division of Yamna settlers needs not be 50:50 for L51:Z2103, either in time or in space. I think this is the simplistic view underlying many thoughts on this matter. Many different expanding patrilineal clans of L23 subclades may have been more or less successful in different areas, and non-Z2103 may have been on the minority, or more isolated relative to Z2103-clans among expanding peoples on the steppe, especially on the east. In fact, we usually talk in terms of “Z2103 vs. L51” as if

- these two were the only L23 subclades; and

- both had split and succeeded (expanding) synchronously;

that is, as if there had not been multiple subclades of both haplogroups, and as if there had not been different expansion waves for hundreds of years stemming from different evolving nuclei, involving each time only limited (successful) clans. Many different subclades of haplogroups L23 (xZ2103, xL51), Z2103, and L51 must have been unsuccessful during the ca. 1,500 years of late Khvalynsk and late Repin-Early Yamna expansions in which they must have participated (for approximately 60-75 generations, based on a mean 20-25 years).

- If we want to imagine a pocket of ‘hidden’ L51 for some region of the North Pontic or Carpathian region, the same can be imagined – and much more likely – for any unsampled territory of expanding late Repin/Early Yamna settlers from the Lower Don – Lower Volga region (probably already a mixed society of L51 and Z2103 subclades since their beginning, as the early Repin culture, ca. 3800 BC), with L51 clans being probably successful to the west.

- The Repin culture expanded only in small, mobile settlements from the Lower Don – Lower Volga to the north, east, and south, starting ca. 3500/3400 BC, in the waves that eventually gave a rather early distant offshoot in the Altai region, i.e. Afanasevo. Starting ca. 3300 BC in the archaeological record, the majority of R1b-Z2103 subclades found to date in Afanasevo also supports either

- a mixed Repin society, with Z2103-clans predominating among eastern settlers; or

- a Repin society marked by haplogroup L51, and thus a cultural diffusion of late Repin/Early Yamna traits among neighbouring (Khvalynsk, Samara, etc.) groups of essentially the same (early Khvalynsk-Novodanilovka) genetic stock in the Volga–Ural region.

Both options could justify a majority of Z2103 in the Lower Volga–Ural region, with the latter being supported by the scattered archaeological remains of late Repin in the region before the synchronous emergence of Early Yamna findings in the whole Pontic-Caspian steppe.

- Most Z2103 from Yamna samples to date are from around 3100 BC (in average) onward, and from the right bank of the Lower Don to the east, particularly from the Lower Volga–Ural area (especially the Samara region), which – based on the center of expansion of late Repin settlers – may be depicting an artificially high Z2103-distribution of the whole Yamna community.

- Yamna sample I0443, R1b-L23 (Y410+, L51-), ca. 3300-2700 BCE from Lopatino II, points to an intermediate subclade between L23 and L51, near one of the supposed late Repin sites (based on kurgan burials with late Repin cultural traits) in the Samara region.

- Other Balkan cultures potentially unrelated to the Yamna expansion also show Z2103 (and not only L51) subclades, like I3499 (ca. 2884-2666 calBC), of the Vučedol culture, from Beli Manastir-Popova zemlja, which points to the infiltration of Yamna peoples in other cultures. In any case, the appearance of R1b-L23 subclades in the region happens only after the Yamna expansion ca. 3100 BC, probably through intrusions into different neighbouring regions, if these Balkan cultures are not directly derived from Yamna settlements (which is probably the case of the Csepel Bell Beaker or early Nagýrev sample, see above).

- The diversity of haplogroups found in or around the Carpathian Basin in Late Chalcolithic / Early Bronze Age samples, including L151(xP312, xU106), P312, U106, Z2103, makes it the most likely sink of Yamna settlers, who spread thus with expanding family clans of different R1b-L23 subclades.

- Even though some Yamna vanguard groups are known to have expanded up to Saxony-Anhalt before ca. 2700 BC, haplogroup Z2103 seems to be restricted to more eastern regions, which suggests that R1b-L51 was already successful among expanding West Yamna clans in Hungary, which gave rise only later to expanding East Bell Beakers (overwhelmingly of L151 subclades). The source of R1b-L51 and L151 expansion over Z2103 must lie therefore in the West Yamna period, and not in the Bell Beaker expansion.

- The R1b-Z2103 found in Poltavka, Catacomb, and to the south point to a late migration displacing the western R1b-L51, only after the late Repin expansion. This is also seen in the steppe ancestry and R1b-Z2103 south of the Caucasus, in Hajji Firuz, which points to this route as a potential source of the supposed “Earliest Proto-Indo-Iranian” (the mariannu term) of the Near East. A similar replacement event happened some centuries later with expanding R1a-Z93 subclades from the east wiping out haplogroup R1b-Z2103 from the Pontic-Caspian steppe.

- Many ancient samples from Khvalynsk, Northern Caucasus, Yamna, or later ones are reported simply as R1b-M269 or L23, without a clear subclade, so the simplistic ‘Yamna–Z2103’ picture is not real: if one takes into account that Z2103 might have been successful quite early in the eastern region, it is more likely to obtain a successful Y-SNP call of a Z2103 subclade in the Volga–Ural region than a xZ2103 one.

- There are some modern samples of R1b-L51 in eastern Europe and Asia, whose common simplistic attribution to “late expansions” is usually not substantiated; and also ancient R1b-L51 samples might be confirmed soon for Asia.

- ‘Western’ features described by archaeologists for West Yamna settlers, associated with Kemi Oba and southern Yamna groups in the North Pontic area – like rich burials with anthropomorphic stelae and wagons – are actually absent in burials from settlers beyond Bulgaria, which does not support their affiliation with these local steppe groups of the Black Sea. Also, a mix with local traditions is seen accross all Early Yamna groups of the Pontic-Caspian steppe, and still genetics and common cultural traits point to their homogeneization under the same patrilineal clans expanding continuously for centuries. The maintenance of local traditions (as evidenced by East Bell Beakers in Iberia related to Iberian Proto-Beakers) is often not a useful argument in genetics, especially when the female population is not replaced.

Conclusion

This is what we know, using linguistics, archaeology, and genetics:

- Middle Proto-Indo-European expanded with Khvalynsk-Novodanilovka after ca. 4800 BC, with the first Suvorovo settlements dated ca. 4600 BC.

- Archaic Late Proto-Indo-European expanded with late Repin (or Volga–Ural settlers related to Khvalynsk, influenced by the Repin expansion) into Afanasevo ca. 3500/3400 BC.

- Late Proto-Indo-European expanded with Early Yamna settlers to the west into central Europe and the Balkans ca. 3100 BC; and also to the east (as Pre-Proto-Indo-Iranian) into the southern Urals ca. 2600 BC.

- North-West Indo-European expanded with Yamna Hungary -> East Bell Beakers, from ca. 2500 BC.

- Proto-Indo-Iranian expanded with Sintashta, Potapovka, and later Andronovo and Srubna from ca. 2100 BC.

It seems that the subclades from Khvalynsk ca. 4250-4000 BC were wrongly reported – like those of Narasimhan et al. (2018). However, even if they are real and YFull estimates have to be revised, and even if the split had happened before the expansion of Suvorovo-Novodanilovka, the most likely origin of R1b-L51 among Bell Beakers will still be the expansion of late Repin / Early Yamna settlers, and that is what ancient DNA samples will most likely show, whatever the social or political consequences.

The only relevance of the finding of R1b-L51 in one place or another – especially if it is found to be a remnant of a Middle PIE expansion coupled with centuries of admixture and interaction in the Carpathian Basin – is the potential influence of an archaic PIE (or non-IE) layer on the development of North-West Indo-European in Yamna Hungary -> East Bell Beaker. That is, more or less like the Uralic influence related to the appearance of R1a-Z93 among Proto-Indo-Iranians, of R1a-Z284 among Pre-Germanic peoples, and of R1a-Z282 among Balto-Slavic peoples.

I think there is little that ancient DNA samples from West Yamna could add to what we know in general terms of archaeology or linguistics at this point regarding Late PIE migrations, beyond many interesting details. I am sure that those who have not attributed some random 6,000-year-old paternal ancestor any magical (ethnic or nationalist) meaning are just having fun, enjoying more and more the precise data we have now on European prehistoric populations.

As for those who believe in magical consequences of genetic studies, I don’t think there is anything for them to this quest beyond the artificially created grand-daddy issues. And, funnily enough, those who played (and play) the ‘neutrality’ card to feel superior in front of others – the “I only care about the truth”-type of lie, while secretly longing for grandpa’s ethnolinguistic continuity – are suffering the hardest fall.

Related

- Trypillia and Greece Neolithic outliers: the smoking gun of Proto-Anatolian migrations?

- Corded Ware culture origins: The Final Frontier

- Sredni Stog, Proto-Corded Ware, and their “steppe admixture”

- Kurgan origins and expansion with Khvalynsk-Novodanilovka chieftains

- About Scepters, Horses, and War: on Khvalynsk migrants in the Caucasus and the Danube

- Steppe and Caucasus Eneolithic: the new keystones of the EHG-CHG-ANE ancestry in steppe groups

- The Caucasus a genetic and cultural barrier; Yamna dominated by R1b-M269; Yamna settlers in Hungary cluster with Yamna

- The concept of “Outlier” in Human Ancestry (III): Late Neolithic samples from the Baltic region and origins of the Corded Ware culture

- Consequences of Damgaard et al. 2018 (II): The late Khvalynsk migration waves with R1b-L23 lineages

- On the potential origin of Caucasus hunter-gatherer ancestry in Eneolithic steppe cultures

- Eneolithic Ukraine cultures of the North Pontic steppe and southern steppe-forest, on the Left Bank of the Dnieper

- North Pontic steppe Eneolithic cultures, and an alternative Indo-Slavonic model

- New Ukraine Eneolithic sample from late Sredni Stog, near homeland of the Corded Ware culture

- The renewed ‘Kurgan model’ of Kristian Kristiansen and the Danish school: “The Indo-European Corded Ware Theory”