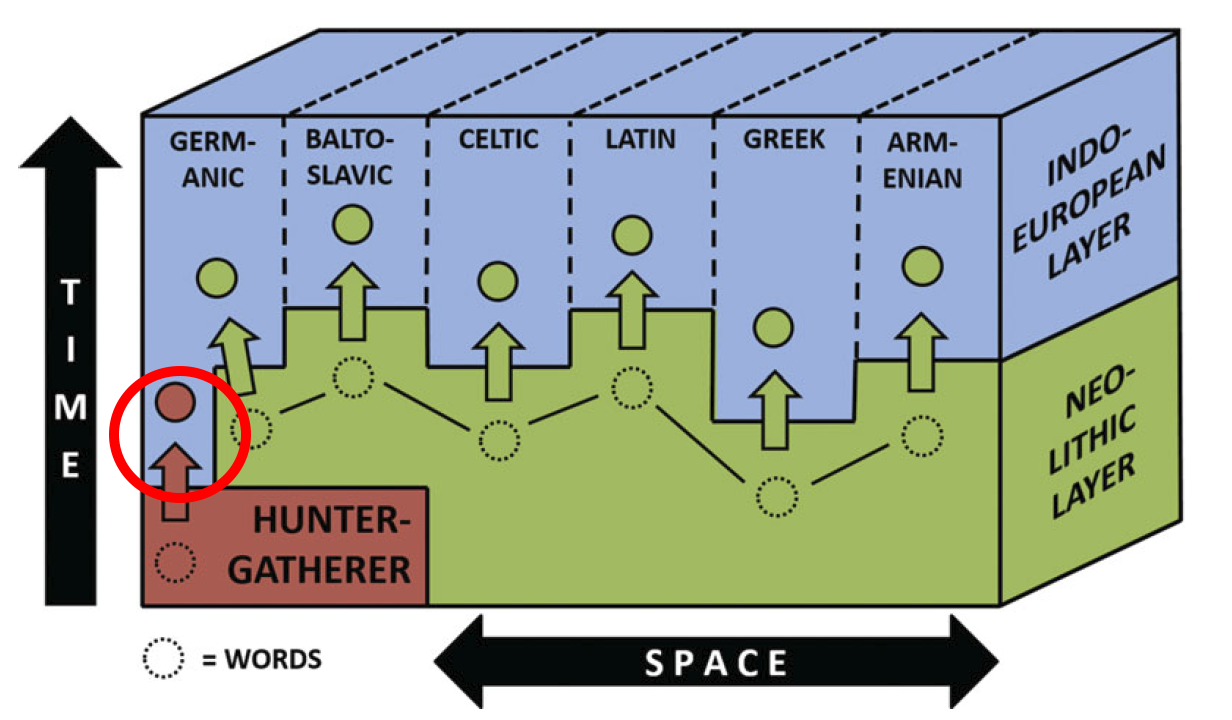

I said I would write a post about topo-hydronymy in Europe and Iberia based on the most recent research, but it seems we can still enjoy some more discussions about the famous Vasconic Beakers, by people longing for days of yore. I don’t want to spoil that fun with actual linguistic data (which I already summarized) so let’s review in the meantime one of the main Uralic-Indo-European interaction zones: Scandinavia.

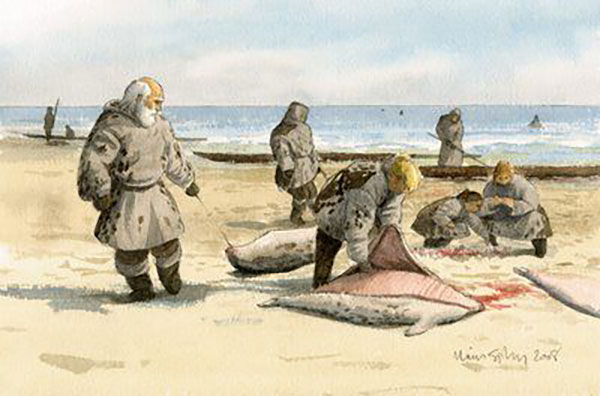

Seal hunting

One of the many eye-catching interpretations – and one of the few interesting ones – that could be found in the relatively recent article Talking Neolithic: Linguistic and Archaeological Perspectives on How Indo-European Was Implemented in Southern Scandinavia, by Iversen & Kroonen AJA (2017) was this:

The borrowing of lexical items from hunter-gatherers into Germanic refers to the potential adoption of Proto-Germanic *selhaz “seal” (Old Norse selr, Old English seolh, Old High German selah) as well as Early Proto-Balto-Finnic *šülkeš “seal” (Finnish hylje, Estonian hüljes) from the marine-oriented Sub-Neolithic Pitted Ware culture.

This is what Kroonen thought about this word in his Etymological Dictionary of Proto-Germanic (2006):

Gmc. *selha– m. ‘seal’ – ON selr m. ‘id.’, Far. selur m. ‘id.’, OSw. siæl m. ‘id.’, Sw. själ c. ‘id.’, OE seolh m. ‘id.’, E seal, OS selah m. ‘id.’, EDu. seel, seel-hont m. ‘id.’, Du. zee-hond c. ‘id.’, OHG selah m. ‘id.’, MHG sele m. ‘id.’ (GM).

A Germanic word with no certain IE etymology. The link with Lith. selė́ti ‘to crawl’ (Torp 1909: 436) is erroneous, as this verb corresponds to PGm. *stelan- (q.v.). The *h may nevertheless correspond to the PIE animal suffix *-ko-, for which see *elha{n)- ‘elk’ and *baruga- ‘boar’.

Focusing on this substrate etymon, coupled with archaeology and ancient DNA, in the recent SAA 84th Annual Meeting (Abstracts in PDF):

Kroonen, Guus (Leiden University) and Rune Iversen

[196] The Linguistic Legacy of the Pitted Ware Culture

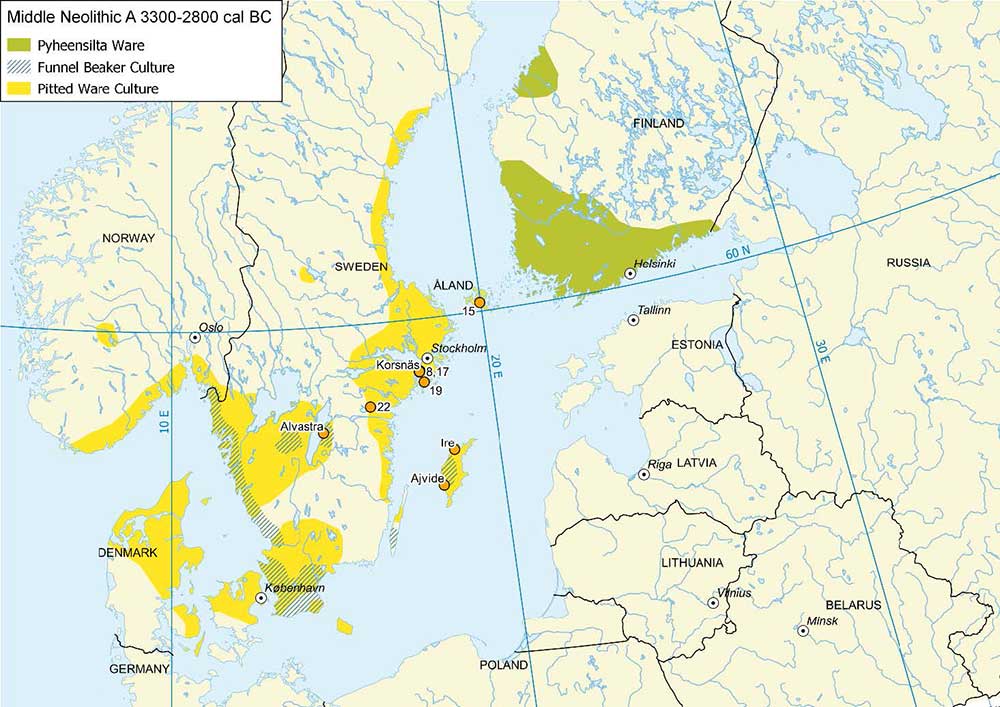

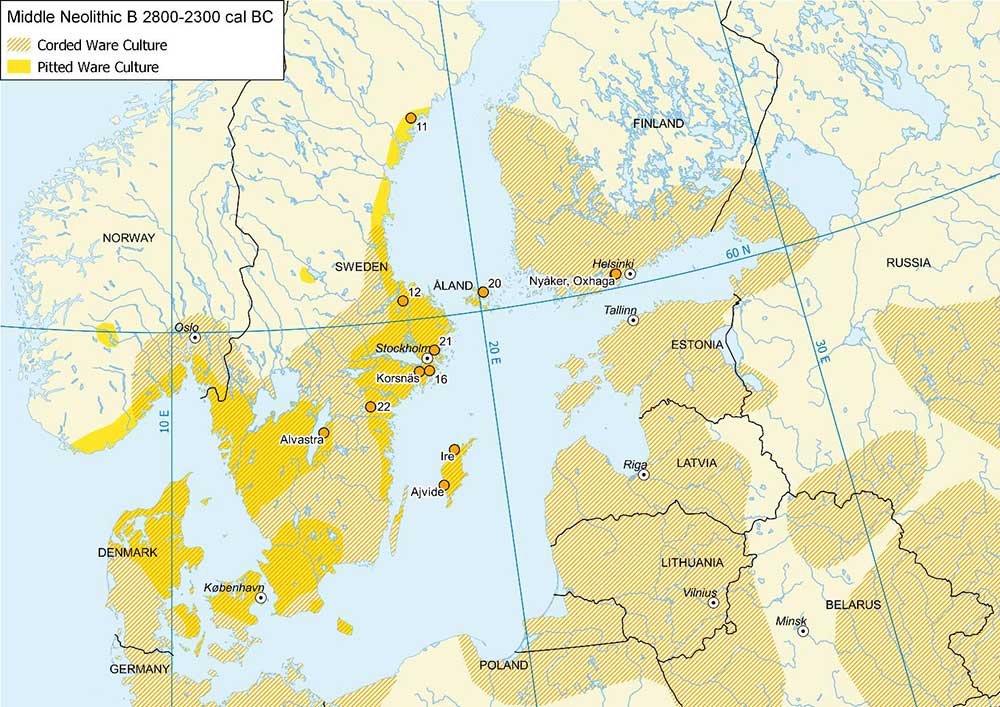

The Scandinavian hunter-, fisher- and gatherer-based Pitted Ware culture is chronologically situated in the Neolithic. However, it challenges our traditional view on cultural and social evolution by representing a return to an otherwise abandoned hunter-gatherer lifestyle. In general, the Pitted Ware culture must be seen as an offshoot of the “Sub-Neolithic” societies inhabiting wide parts of northern and northeastern Europe in the fourth and third millennium B.C.E.

Isotopic and aDNA studies have shown that people of the east Swedish Pitted Ware culture, both dietarily and genetically were distinct from the early farmers in this region, the Funnel Beaker culture. Isotopic data shows a marked predominance of seal in the diet, which has given the Pitted Ware people the nickname “Inuit of the Baltic”.

As regards language, it is to be expected that people practicing a Pitted Ware lifestyle spoke a non-Indo-European language. In fact, there is some linguistic evidence that can support this claim. It is conceivable that both the Germanic and Finnish word for “seal” were ultimately borrowed from a language spoken in a Pitted Ware context. Once more, the linguistic evidence turns out to offer important information complementary to that of archaeology and archaeo-genetics.

Apparently, the idea of non-IE substrate languages in contact with Germanic in Scandinavia is fashionable for the Copenhagen group, probably due to their particular interpretation of the recent genetic papers, hence the multiple Germanic-Fennic connections to be reviewed through this new prism. While the ulterior motive of this proposal may be to try and connect yet again Germanic with CWC Denmark, I would argue that the effect is actually the opposite.

An early borrowing via Uralic

The word has always been considered a more likely loan from one language to the other, and – because of the quite popular idea of Uralic native to Fennoscandia – it was often seen as a likely borrowing of Germanic from Balto-Finnic. In any possible case, the borrowing in either direction must be quite early, for obvious reasons:

- If the borrowing had been via late Palaeo-Germanic, the ending in *-xa– would have been reflected in Balto-Finnic, hence an early Palaeo-Germanic to Pre-Balto-Finnic stage would be necessary.

- If the borrowing had been via late Balto-Finnic, the initial sibilant would be already aspirated, being adopted as *-x– in Palaeo-Germanic, while the ending in *-k– would have remained as such if it was adopted after Grimm’s law ceased to be active.

- Similarly, a borrowing from a common, non-Indo-European & non-Uralic source would require that it happened during the early stages of both proto-languages to have undergone their respective phonetic changes, and both borrowings chronologically close to each other, to assume a similar vocalism and consonantism of the ultimate source.

Furthermore, regarding the most likely way of expansion of this loanword, due to the different vowels and sibilants present in Uralic but not in Indo-European:

- A direct loan from Pre-Germanic **selkos – which shows a regular thematic declension – to Pre-Balto-Finnic *šülkeš doesn’t seem to be a reasonable assumption.

- If we reconstruct an older Pre-Finno-Samic (i.e. with Finno-Permic-like vocalism) **šëlkëš, a borrowing into Pre-Germanic **selkos would work. Even though no Saami derivative exists to confirm such a possibility, this would be supported by the known common evolution of Finno-Samic dialects in close contact with Pre-Germanic.

- Admittedly, even accepting the existence of a Finno-Samic stem, a potential substrate word could not be discarded. In fact, while **šëlkë- could perfectly be a Uralic root, the ending in *-š can’t be easily interpreted. Therefore, a third, non-Indo-European & non-Uralic source is a plausible explanation.

NOTE. A Germanic borrowing from alternative Gmc. genitive *silxis could only work in a Pre-Germanic to Pre-Balto-Finnic model, hence only if the Gmc. form can be reconstructed for an earlier stage. Even then, for the same reason stated above, the opposite could be more reasonably argued, i.e. that this form is the original one adopted in Germanic: Pre-PBF *šülkeš > Pre-Gmc. *silkis, reinterpreted as an -o- stem in its declension.

NOTE. Arguably, Proto-Finno-Samic could have adopted Gmc. *kh or *x exceptionally as PFS *k. However, early Palaeo-Germanic borrowings in Finno-Samic show a consistent regular consonant change as described above. For more on this, see Finno-Samic borrowings.

This likely Uralic first nature of the loanword is important for the discussion below.

Pitted Ware culture

About the Pitted Ware culture, this is what the recent paper by Vanhanen et al. (2019), from the University of Finland (including Volker Heyd) had to say:

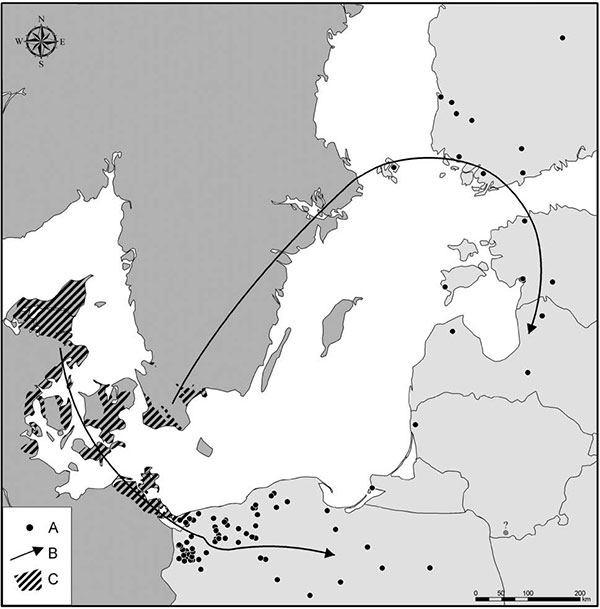

The origins of the PWC are controversial. In one likely scenario, Comb Ceramic and Mesolithic hunter-gatherers first interacted with FBC during the last centuries of the EN and became specialized maritime hunter-gatherers. The PWC pushed south and westwards during the Middle Neolithic (MN), c. 3300–2300 BC, along the northern Baltic shoreline and adjacent islands, eventually reaching as far west as Denmark and southern Norway. Around 2800 BC, after the FBC ceased to exist, the Corded Ware Culture (CWC) migrated into the PWC area. The end date for the PWC and CWC is approximately 2300 BC, when the material culture was replaced by the Late Neolithic (LN) culture<. Spanning nearly a millennium virtually unchanged, the PWC maintained a coherent society and a successful economic model. PWC people lived in marine-oriented settlements, commonly dwelled in huts and produced relatively large amounts of ceramic vessels. This speaks to the partly sedentary nature of their habitation, at least for their base camps. These specialist hunter-gatherers obtained the great majority of their subsistence from maritime sources, such as seal, fish, and sea birds. Considering the amount of bones, sealing was of paramount importance, causing these peoples to be labelled ‘hard-core sealers’ or even the ‘Inuit of the Baltic’.

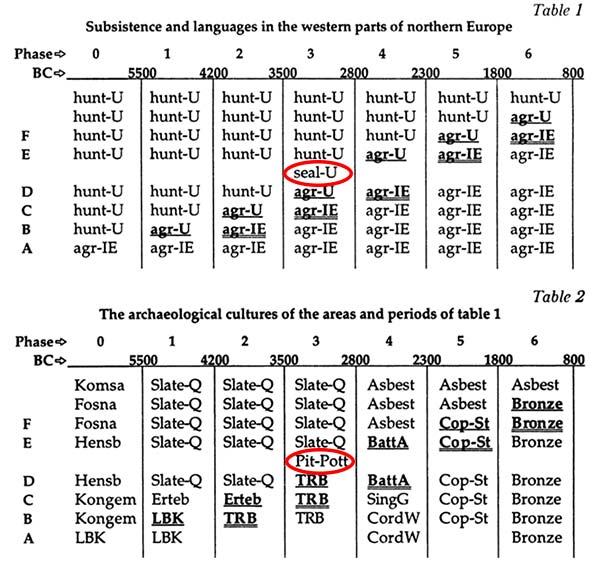

The Middle Neolithic Pitted Ware culture is dated ca. 3500–2300 BC, so we would be seeing here Pre-Germanic and Pre-Balto-Finnic peoples arriving near the Pitted Ware culture. That would leave us with one of both languages expanding with Corded Ware peoples, and the other with Bell Beakers. Since Battle Axe-derived cultures around the Gulf of Finland are associated with Balto-Finnic groups, and Bell Beakers arriving ca. 2400 started the Dagger Period, commonly associated with the Pre-Germanic community, I think the connection of each group with their language is self-evident.

NOTE. You can read some interesting information about prehistoric and recent seal hunting in the Baltic in the blog post “Själen” – Seal Hunting in the Northern Baltic Sea.

Germanic-Fennic phonetic evolution

The common Germanic – Balto-Finnic phonetic evolution, especially Verner’s law in Palaeo-Germanic and qualitative gradation in Proto-Balto-Finnic, has been variably interpreted as:

- Uralic in Scandinavia influenced by Germanic (Verner’s law source of the gradation), by Koivulehto and Vennemann (1996).

- Germanic over a Uralic substratum in Scandinavia, by Wiik (1997).

- Both Germanic and Balto-Finnic influenced by a third language, an “extinct non-Uralic source” spoken in Fennoscandia before the arrival of Uralic and Indo-European, by Kallio (2001); maybe the same substrate proposed to have influenced the accent shift in Germanic similar to Uralic.

- Balto-Finnic speakers adopting Pre-Germanic in Scandinavia, in contact with Balto-Finnic speakers retaining their language, by Schrijver in Language Contact and the Origins of the Germanic Languages (2014)– although first suggested by him in the 1990s.

NOTE. There are other (some much older) proposals of a Uralic substrate in Scandinavia, but I think those above summarize the most common positions tenable today.

If you add all linguistic, archaeological, and now genetic connections, it is really strange to keep arguing for so many surprisingly fitting common substrates and/or contact languages for both. Especially because the Pre-Germanic community – if originally from southern Scandinavia and not further south (see e.g. Kortlandt’s theory) – was marked by the Dagger Period, as accepted by most archaeologists (including Kristiansen), and we know that Bell Beakers – who triggered the Dagger period – might have arrived a little late to the Pitted Ware disintegration in most seal-hunting areas of southern Scandinavia.

In other words, how many common substrate languages can we propose for Germanic (and Balto-Finnic)? Just from Kroonen we have already the Semitic-like TRB, and the seal-hunting Pitted Ware culture. Apparently, the culprit of the common phonetic evolution must be some (other?) culture that both Pre-Germanic and Pre-Balto-Finnic assimilated (or with which both were in contact) in Fennoscandia.

NOTE. I believe no data supports the attribution of those Germanic borrowings to the TRB culture, especially if one assumes they belong to an Afroasiatic branch, as did Kroonen. His initial assumption about an expansion of R1b-M269 associated with the Neolithic from Anatolia, and thus with Afroasiatic, must today be rejected. Much more likely is the incorporation of most of these loanwords during the expansion of North-West Indo-Europeans from Yamna Hungary.

How many “common” substrates from different regions and cultures is too much? Arguably, it’s not a question of quantity (because the overall probability remains the same), but a question of quality of arguments.

In my opinion, both a) the marked seal-hunting subsistence economy of the Pitted Ware culture and b) the difficult reconstruction of a fitting ‘natural’ PIE or PU stem warrant this proposal of a third source, just like the European agricultural substrate of North-West Indo-European and Palaeo-Balkan languages, as well as the Asian agricultural substrate of Indo-Iranian are the most logical interpretation of words not found in other IE dialects. The only problem in this case is the lack of other Scandinavian substrate words to compare its typology against.

Common Scandinavian substratum

The theory of a Pitted Ware borrowing is therefore quite convincing from a cultural point of view, at the same time as it fits the linguistic data. However, one reason why I dislike the interpretation of a dual origin is that our knowledge of Uralic languages is fairly limited, whereas that of Indo-European branches and hence Proto-Indo-European is huge. To put it otherwise: if a common word appears in both, and it is most likely (culturally and linguistically) not Indo-European, it certainly means that it was borrowed in Germanic. What are the a priori chances of it coming directly from a third substrate language for both dialects, instead of coming directly from Pre-Balto-Finnic?

From Schrijver (2014):

What did happen, apparently, is that Finnic speakers had enough access to the way in which Germanic speakers pronounced Balto-Finnic in order to model their own pronunciation of Balto-Finnic on it. In other words, Balto-Finns conversed with bilingual speakers of Germanic and Balto-Finnic whose pronunciation of both was essentially Germanic. But access to the Germanic language itself was not sufficient to allow Balto-Finns to become bilingual themselves, either because social segregation prevented this or because contact with Germanic was severed before widespread bilingualism set in. This limited access to Germanic would allow us to understand why Balto-Finnic did not go the way of the vernacular languages that came in contact with Latin in the Roman Empire, where access to Latin was open to almost everybody and massive language shift in favour of Latin ensued.

NOTE. For a more detailed discussion, you can read the whole chapter dedicated to this question. I summarized it in Pre-Germanic born out of a Proto-Finnic substrate in Scandinavia.

On the other hand, about the ad hoc interpretation by Kallio (2001) of hypothetic third languages strongly influencing in the same way both the Palaeo-Germanic- and Balto-Finnic-speaking communities, Schrijver (2014) comments:

The idea that perhaps both languages moved towards a lost third language, whose speakers may have been assimilated to both Balto-Finnic and Germanic, provides a fuller explanation but suffers from the drawback that it shifts the full burden of the explanation to a mysterious ‘language X’ that is called upon only in order to explain the developments in Proto-Germanic and Balto-Finnic. That comes dangerously close to circular reasoning.

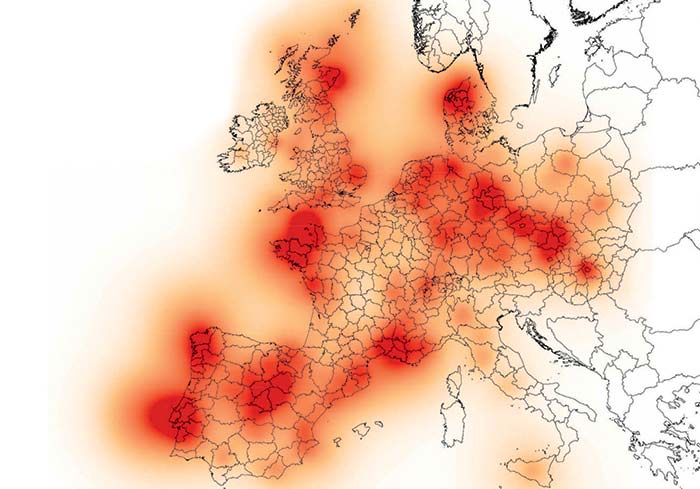

NOTE. The proposal of some kind of “SHG/EHG-based Fennoscandian substrate” seems funny to me, for two reasons: firstly, there is usually no talk about which culture spread that common language, how it survived, how it was in contact with both groups and until when, etc. (see below for possibilities); secondly, apparently the evident survival of West European EEF communities driven by at least two cultural groups – El Argar and the poorly known groups from the Atlantic façade north of the Pyrenees – is, for the same people proposing this simplistic SHG/EHG idea, somehow not fitting for the prehistory of Proto-Iberian and Proto-Aquitanian, respectively…

The same argument that one could use against the direct borrowing of both dialects from Pitted Ware, but much more strongly, can be thus wielded against a common, centuries-long phonetic evolution of both Balto-Finnic and Germanic caused by close interactions with (and/or substrate influence of) some third language. Which unitary culture and when exactly could that have happened around the Baltic Sea?

- Was it Pitted Ware the mysterious substrate language? Seems rather unlikely, due to the early demise of the Pitted Ware culture in contrast to the long-lasting common influence seen in both dialects.

- Was it Pitted Ware in southern Scandinavia, but Comb Ware in the Gulf of Finland? Is there a direct genetic connection between both cultures? And how likely is a common phonology of an ancestral Comb Ware-like substrate language surviving separately in Finland and Sweden? Even accepting these assumptions, we would be stuck again in the Indo-European Beakers vs. Uralic Battle Axe model.

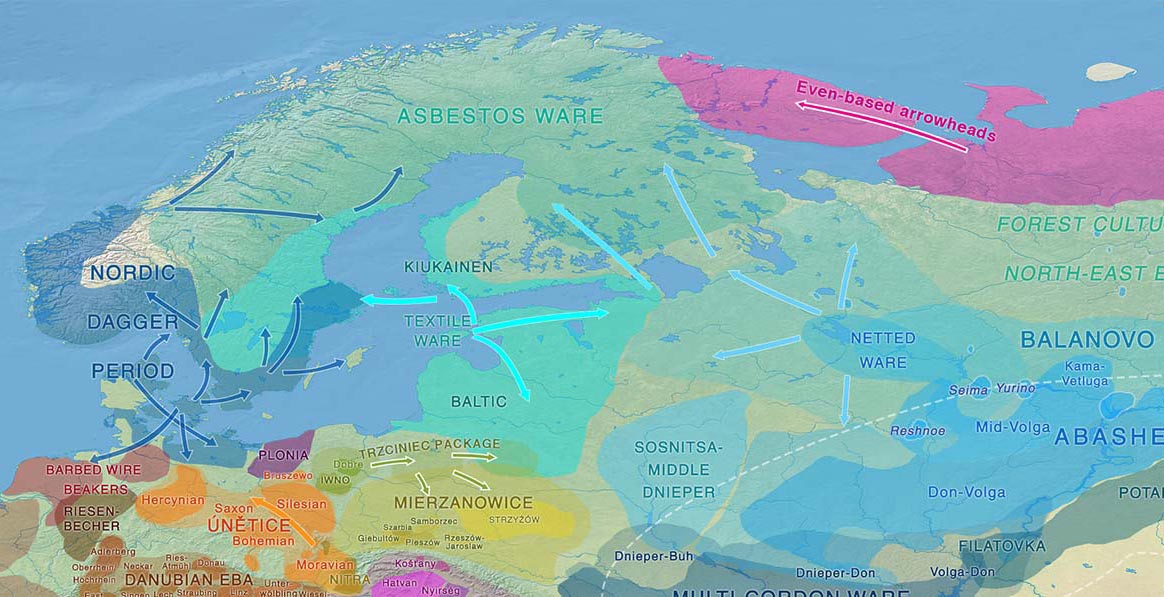

- Was it a succession of cultures, from some Scandinavian culture that was replaced by some incoming ethnolinguistic group, then influencing the other? This non-IE, non-Uralic substrate would then need to be proposed, given the chronological and archaeological constraints, as an effect of Pitted Ware over Pre-Finno-Baltic spoken by Battle Axe peoples in Scandinavia, then replaced by Pre-Germanic peoples arriving later with Bell Beakers. A reverse direction and later chronology (say, Germanic replaced by Balto-Finnic from Netted Ware arriving from the Volga) wouldn’t work as well.

- Was it Asbestos Ware as a late Comb Ware group influencing both? How likely is such a continued influence in Southern Scandinavia and the Gulf of Finland? Even if we accepted this influence that miraculously didn’t affect Samic (most likely located between the Balto-Finnic-speaking Gulf of Finland and northern Fennoscandian Asbestos Ware groups), it would necessarily mean that Germanic and Balto-Finnic were spoken neighbouring exactly the same Asbestos Ware groups in Scandinavia. That is, essentially, that the BBC-derived Dagger Period represented Pre-Germanic, while Battle Axe-derived groups around the Gulf of Finland were Balto-Finnic.

Mixing linguistics with archaeology (now complemented with genetics) also risks circular reasoning. But, how else can someone propose a third substrate language for a phonetic change, necessarily represented by Fennoscandian groups potentially separated by thousands of years? In this age of population genomics we can’t simply talk about theoretical models anymore: we must refer to Fennoscandian cultures and populations in a very specific time frame, as Kronen & Iversen do in their proposal. Not only is such a third unknown language usually a weak explanation for a common development of two unrelated languages; in this case it finds no support whatsoever.

Seals and the Arctic

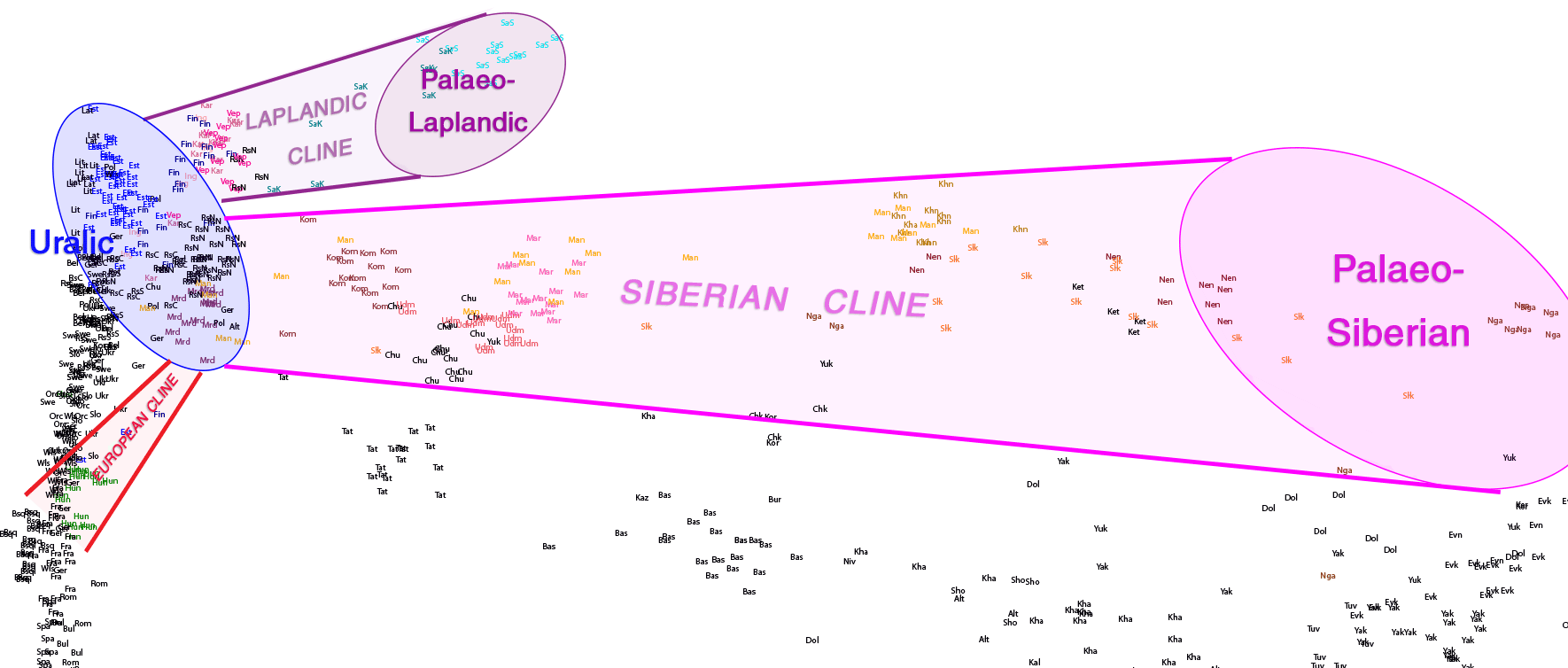

Another interesting aspect about this Fennic-Germanic comparandum is its relevance to the Uralic homeland problem.

Since the publication of Mittnik et al. (2018), Lamnidis et al. (2018), and Sikora et al. (2018), the new normal is apparently to consider Corded Ware Finland as Germanic-speaking, the Gulf of Finland as Balto-Slavic-speaking, while the Kola peninsula and whichever Palaeo-Arctic peoples preceded Nganasans and Nenets as ancient Uralians. Uh-huh, OK.

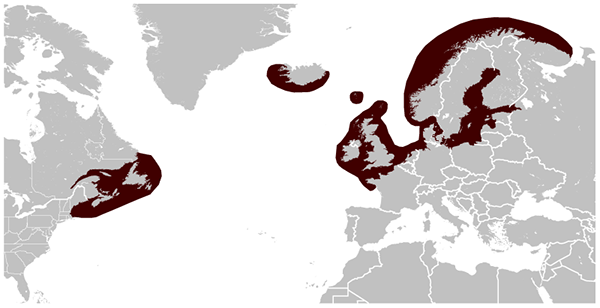

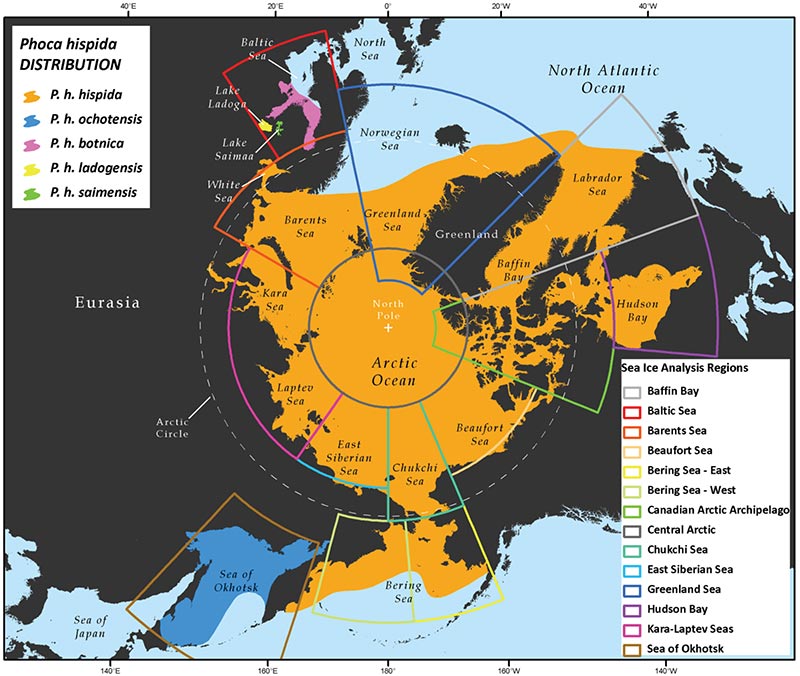

But, if prehistoric Arctic peoples practiced specialized seal-hunting economies, and Uralians were one among such populations – supposedly one widespread from the Barents Sea to the Lapteve Sea…how come no common Uralic word for ‘seal’ exists? In other words, why would these True™ Uralic peoples expanding from the Arctic need to borrow a word for ‘seal’ from neighbouring populations in every single seal-hunting region they are attested?

About Saami, which some have recklessly proposed to be derived from Bronze Age N1c-L392 samples from the Kola Peninsula (against the good judgment of the authors of the paper), this is what we know from their word for ‘seal’, from Grünthal (2004):

Ter Saami vīrre ‘seal; wolf’ displays two meanings that refer to clearly different animals. Neither of them is borrowed from the source language because the word descends from Russian zver’ ‘animal’ (T.I.Itkonen 1958: 756). Another word, Skolt Saami näúdd ‘seal, wolf’, has been similarly used in the two meanings. The evidence of North Saami návdi ‘wolf; creature, fur animal; beast’ (Sammallahti 1989: 305; Lagercrantz (1939: 518) presents the alternative meanings in the opposite order; E. Itkonen (1969: 148) lists the meanings ‘wildes Tier; Raubtier (bes. Wolf); Pelztier’) suggesting that ‘wolf’ is the primary sense and ‘seal’ is a metaphorical extension of it. More precisely, it is an example of a mythic metaphor (cf. Siikala 1992). According to the old folk belief, seal was a wolf and the Skolt Saamis preferred not to eat its meat (T.I.Itkonen 1958: 906). Before that the metonymic meaning ‘wolf’ rose from the less specified meanings, and originally návdi is a Scandinavian or Finnic loan word in Saamic, cf. Old Norse naut ‘vieh, rind’, Icelandic and Norwegian naut, Swedish nöt < Germanic *nauta ‘property’ (Hellquist 1980: 721, T.I.Itkonen 1958: 275, Lagercrantz 1939: 518, de Vries 1961: 406; E. Itkonen (1969: 148) considers Finnic, cf. Finnish nauta ‘bovine’ (< Germanic) as a possible alternative source for the Saamic word).

NOTE. Possibly comparable, for the mythic metaphor proper of Scandinavian folk belief, are Germanic derivatives built as ‘seal-hound’ and/or ‘sea-hound’.

About Nenets (quite close to the Naganasans of pure “Siberian ancestry”), here is what Edward Vajda, an expert in Palaeo-Siberian languages, has to say:

Nenets techniques for hunting the animals of the Arctic Ocean seem to have been borrowed from the first Arctic aborigines. Thus, the Nenets word for seal is nyak, the Eskimo word is nesak. Also, the Nenets word for a one-piece Arctic clothing is lu; the Korak word on the Kamchatka peninsula for clothing is l’ku. All of these groups may have borrowed the words from some original circumpolar aborigines. More probably, the first settlers of Arctic Europe were cousins of the present-day Eskimo, Chukchi and other residents of the far northeast region of Asia. Nenets folklore also speaks of the aborigines living in ice dugouts (igloos).

On the other hand, Proto-Uralic shows a Chalcolithic steppe-like culture, with common words for metal and metalworking, for agriculture, and for domesticated animals, most likely including cattle. They were close to Indo-Europeans since at least before the Tocharian split, and probably earlier than that (even if one does not accept the Indo-Uralic phylum). And there were clearly strong contacts of Finno-Ugric with Indo-Iranian, and especially of Finno-Samic with Germanic.

Some among my readers may now be thinking about these totally believable proposals of prehistoric cultures around Lake Baikal representing the True™ Uralic homeland; because haplogroup N1c, and because some 0.5% more “Devil’s Gate Cave ancestry” in Estonians than in Lithuanians; despite the fact that 1) the so-called “Siberian ancestry” formed an ancestral cline with EHG in North Eurasia, that 2) N1c-L392 lineages seem to appear among many Asian peoples of different languages, and that 3) recent prehistoric N1c-L392 lines expanded clearly with Micro-Altaic languages.

Like, who would have hunted seals in Lake Baikal, right? The problem is, seals represented one of their main game, essential for their subsistence economy. From Novokonova et al. (2015):

One of the key reasons for the density of human settlement in the Baikal region compared to adjacent areas of Siberia is that the lake and its nearby rivers offer an abundance of aquatic food resources, including several endemic species, with perhaps the most well known being the Baikal seal. This freshwater seal is only found in Lake Baikal and portions of its tributaries. It shares lifecycle and behavioral patterns with other small northern ice-adapted seals, and is genetically and morphologically most closely related to the ringed seal (Pusa hispida). The nerpa can grow up to 1.8 m long and weigh as much as 130 kg, with the males tending to be slightly larger than the females.

Zooarchaeological analyses of the 16,000 Baikal seal remains from this well-dated site clearly show that sealing began here at least 9000 calendar years ago. The use of these animals at Sagan-Zaba appears to have peaked in the Middle Holocene, when foragers used the site as a spring hunting and processing location for yearling and juvenile seals taken on the lake ice. After 4800 years ago, seal use declined at the site, while the relative importance of ungulate hunting and fishing increased. Pastoralists began occupying Sagan-Zaba at some point during the Late Holocene, and these groups too utilized the lake’s seals. Domesticated animals are increasingly common after about 2000 years ago, a pattern seen elsewhere in the region, but spring and some summer hunting of seals was still occurring. This use of seals by prehistoric herders mirrors patterns of seal use among the region’s historic and modern groups.

Bronze Age movements in Fennoscandia

Regarding the shrinkage and expansion of different farming economic strategies in Scandinavia since the Neolithic, with potential relevance for population movements and thus ethnolinguistic change – either from Balto-Finnic peoples migrating back from eastern Sweden, or Germanic peoples moving to eastern Finland – from Vanhanen et al. (2019):

Cultivated plants at CWC sites in Finland were not discovered in the current investigation (Supplementary Results) or earlier studies. In Finland, the keeping of domestic animals is indicated by the evidence of dairy lipids and mineralized goat hairs. Charred remains and impressions of cultivated plants have been discovered at CWC sites in Estonia and east-central Sweden (Fig. 3: 12). In the eastern Baltic region, the earliest bones of domestic animals and a shift in subsistence occurred with the CWC. Whether CWC produced the cereals and other agricultural products found at PWC sites is difficult to estimate because only small amounts of plant remains have ever been discovered at CWC sites. The CWC seemingly reached east-central Sweden from regions further to the east, where there is evidence of animal husbandry, but only very few signs of plant cultivation.

For the Late Neolithic (LN), cereal grains have been found north of Mälaren and along the Norrland coast. In mainland Finland, the first cereal grains occur during the LN or Bronze Age, c. 1900–1250 cal BC. The earliest bones of sheep/goat from mainland Finland are earlier, dating back to 2200–1950 cal BC. Finds of Scandinavian bronze artefacts indicate an influx from east-central Sweden, which might well be a source area for these agricultural innovations. A similar development is found in the eastern Baltic region, where the earliest directly radiocarbon-dated cereals originate from the Bronze Age, 1392–1123 cal BC (2 sigma). Thus, agriculture was evident during the Bronze Age in the eastern Baltic, but at least animal keeping and probably crop cultivation were present earlier during the CWC phase.

It has been known for a while already that the only options left for the expansion of Finno-Saami into Fennoscandia are either Battle Axe (continued in Textile Ceramics) or Netted Ware (as proposed e.g. by Parpola), based, among other data, on language contacts, language estimates, cultural evolution, and population genomics. Data like this one on seal-hunting vocabulary also support the most likely option, which entails the identification of Corded Ware as the vector of expansion of Uralic languages.

NOTE. Also interesting in this regard is the lack of Slavic words for ‘seal’ – borrowed, in Russian from Samic, and in other Slavic dialects from Russian, Latin, or other languages -, and the coinage of a new term in East Baltic. Rather odd for an “autochthonous” Proto-Baltic (supposedly in contact with Pitted Ware, Germanic, and Balto-Finnic, then), and for a Proto-Slavic stemming from the Baltic. Quite appropriate, though, for a Proto-East Baltic arriving in the Baltic with Trzciniec and for a Proto-Slavic community evolving further south.

So, what new episode in this renewed 2000s R1b/R1a/N1c soap opera is it going to be, when eastern Fennoscandia shows Corded Ware-derived peoples of “steppe ancestry” (and mainly R1a-Z645 lineages) continue during the Bronze Age? Will the resurge and/or infiltration of I2 – maybe even N1c – lineages among Corded Ware-derived cultures of north-eastern Europe support or challenge this model, and why? Make your bet below.

Related

- Kortlandt: West Indo-Europeans along the Danube, Germanic and Balto-Slavic share a Corded Ware substrate

- Pre-Germanic born out of a Proto-Finnic substrate in Scandinavia

- Bell Beaker/early Late Neolithic (NOT Corded Ware/Battle Axe) identified as forming the Pre-Germanic community in Scandinavia

- On Proto-Finnic language guesstimates, and its western homeland

- North-Eastern Europe in the Stone Age – bridging the gap between the East and the West

- Minimal Corded Ware culture impact in Scandinavia – Bell Beakers the unifying maritime elite

- On the origin and spread of haplogroup R1a-Z645 from eastern Europe

- N1c-L392 associated with expanding Turkic lineages in Siberia

- Magyar tribes brought R1a-Z645, I2a-L621, and N1a-L392(xB197) lineages to the Carpathian Basin

- R1a-Z280 and R1a-Z93 shared by ancient Finno-Ugric populations; N1c-Tat expanded with Micro-Altaic

- The complex origin of Samoyedic-speaking populations

- Corded Ware—Uralic (IV): Hg R1a and N in Finno-Ugric and Samoyedic expansions

- Corded Ware—Uralic (III): “Siberian ancestry” and Ugric-Samoyedic expansions

- Corded Ware—Uralic (II): Finno-Permic and the expansion of N-L392/Siberian ancestry

- The traditional multilingualism of Siberian populations

- Haplogroup R1a and CWC ancestry predominate in Fennic, Ugric, and Samoyedic groups

- Oldest N1c1a1a-L392 samples and Siberian ancestry in Bronze Age Fennoscandia