New open access article published in Scientific Reports, Analysis of the R1b-DF27 haplogroup shows that a large fraction of Iberian Y-chromosome lineages originated recently in situ, by Solé-Morata et al. (2017).

Abstract

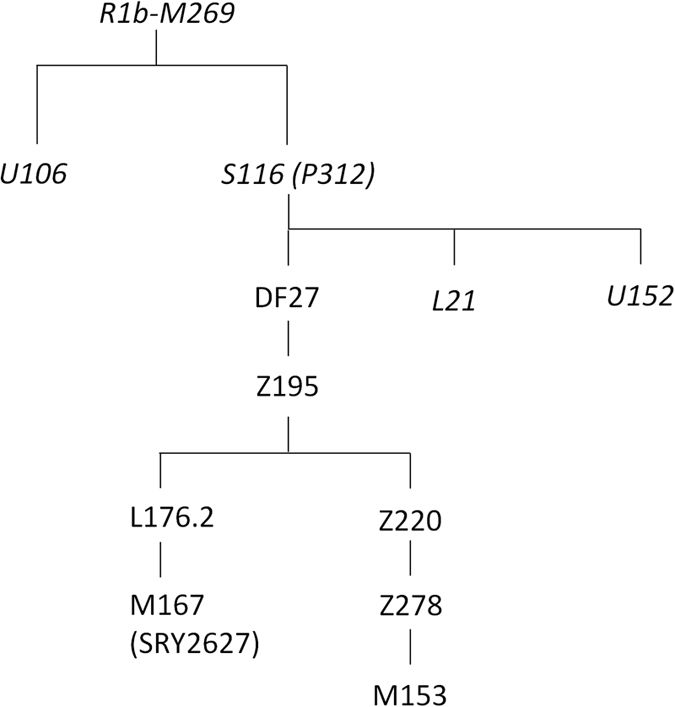

Haplogroup R1b-M269 comprises most Western European Y chromosomes; of its main branches, R1b-DF27 is by far the least known, and it appears to be highly prevalent only in Iberia. We have genotyped 1072 R1b-DF27 chromosomes for six additional SNPs and 17 Y-STRs in population samples from Spain, Portugal and France in order to further characterize this lineage and, in particular, to ascertain the time and place where it originated, as well as its subsequent dynamics. We found that R1b-DF27 is present in frequencies ~40% in Iberian populations and up to 70% in Basques, but it drops quickly to 6–20% in France. Overall, the age of R1b-DF27 is estimated at ~4,200 years ago, at the transition between the Neolithic and the Bronze Age, when the Y chromosome landscape of W Europe was thoroughly remodeled. In spite of its high frequency in Basques, Y-STR internal diversity of R1b-DF27 is lower there, and results in more recent age estimates; NE Iberia is the most likely place of origin of DF27. Subhaplogroup frequencies within R1b-DF27 are geographically structured, and show domains that are reminiscent of the pre-Roman Celtic/Iberian division, or of the medieval Christian kingdoms.

Some people like to say that Y-DNA haplogroup analysis, or phylogeography in general, is of no use anymore (especially modern phylogeography), and they are content to see how ‘steppe admixture’ was (or even is) distributed in Europe to draw conclusions about ancient languages and their expansion. With each new paper, we are seeing the advantages of analysing ancient and modern haplogroups in ascertaining population movements.

Quite recently there was a suggestion based on steppe admixture that Basque-speaking Iberians resisted the invasion from the steppe. Observing the results of this article (dates of expansion and demographic data) we see a clear expansion of Y-DNA haplogroups precisely by the time of Bell Beaker expansion from the east. Y-DNA haplogroups of ancient samples from Portugal point exactly to the same conclusion.

The situation of R1b-DF27 in Basques, as I have pointed out elsewhere, is probably then similar to the genetic drift of Finns, mainly of N1c lineages, speaking today a Uralic language that expaned with Corded Ware and R1a subclades.

The recent article on Mycenaean and Minoan genetics also showed that, when it comes to Europe, most of the demographic patterns we see in admixture are reminiscent of the previous situation, only rarely can we see a clear change in admixture (which would mean an important, sudden replacement of the previous population).

Equating the so-called steppe admixture with Indo-European languages is wrong. Period.

The following are excerpts from the article (emphasis is mine):

Dates and expansions

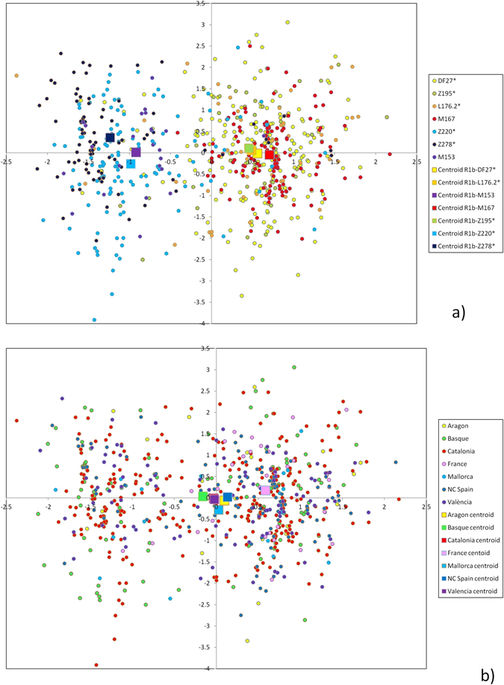

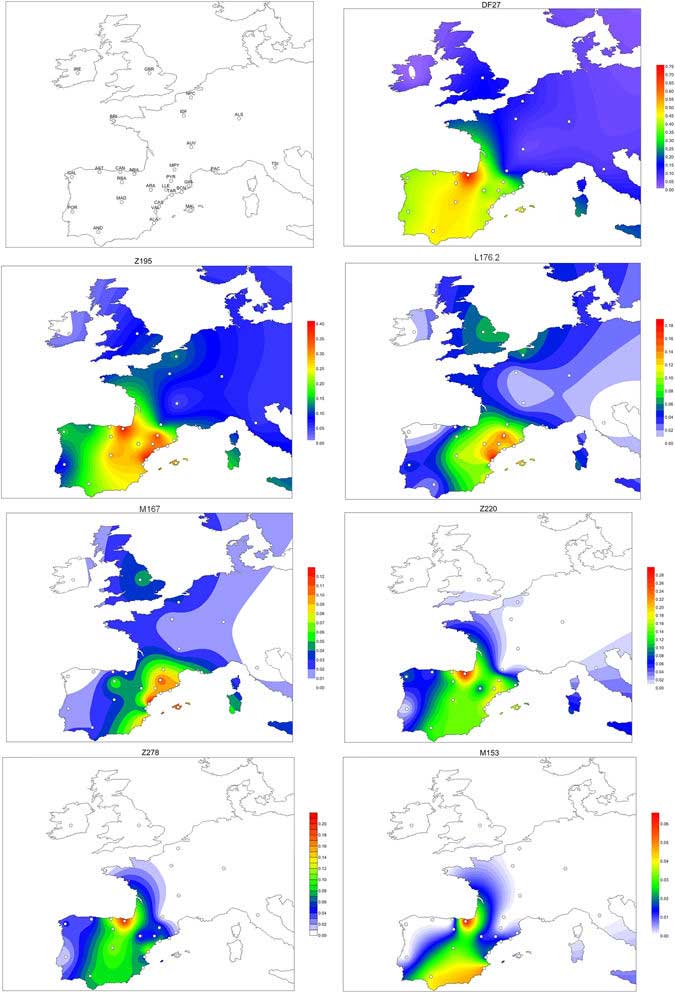

The average STR variance of DF27 and each subhaplogroup is presented in Suppl. Table 2. As expected, internal diversity was higher in the deeper, older branches of the phylogeny. If the same diversity was divided by population, the most salient finding is that native Basques (Table 2) have a lower diversity than other populations, which contrasts with the fact that DF27 is notably more frequent in Basques than elsewhere in Iberia (Suppl. Table 1). Diversity can also be measured as pairwise differences distributions (Fig. 5). The distribution of mean pairwise differences within Z195 sits practically on top of that of DF27; L176.2 and Z220 have similar distributions, as M167 and Z278 have as well; finally, M153 shows the lowest pairwise distribution values. This pattern is likely to reflect the respective ages of the haplogroups, which we have estimated by a modified, weighted version of the ρ statistic (see Methods).

Z195 seems to have appeared almost simultaneously within DF27, since its estimated age is actually older (4570 ± 140 ya). Of the two branches stemming from Z195, L176.2 seems to be slightly younger than Z220 (2960 ± 230 ya vs. 3320 ± 200 ya), although the confidence intervals slightly overlap. M167 is clearly younger, at 2600 ± 250 ya, a similar age to that of Z278 (2740 ± 270 ya). Finally, M153 is estimated to have appeared just 1930 ± 470 ya.

Haplogroup ages can also be estimated within each population, although they should be interpreted with caution (see Discussion). For the whole of DF27, (Table 3), the highest estimate was in Aragon (4530 ± 700 ya), and the lowest in France (3430 ± 520 ya); it was 3930 ± 310 ya in Basques. Z195 was apparently oldest in Catalonia (4580 ± 240 ya), and with France (3450 ± 269 ya) and the Basques (3260 ± 198 ya) having lower estimates. On the contrary, in the Z220 branch, the oldest estimates appear in North-Central Spain (3720 ± 313 ya for Z220, 3420 ± 349 ya for Z278). The Basques always produce lower estimates, even for M153, which is almost absent elsewhere.

Demography

The median value for Tstart has been estimated at 103 generations (Table 4), with a 95% highest probability density (HPD) range of 50–287 generations; effective population size increased from 131 (95% HPD: 100–370) to 72,811 (95% HPD: 52,522–95,334). Considering patrilineal generation times of 30–35 years, our results indicate that R1b-DF27 started its expansion ~3,000–3,500 ya, shortly after its TMRCA.

As a reference, we applied the same analysis to the whole of R1b-S116, as well as to other common haplogroups such as G2a, I2, and J2a. Interestingly, all four haplogroups showed clear evidence of an expansion (p > 0.99 in all cases), all of them starting at the same time, ~50 generations ago (Table 4), and with similar estimated initial and final populations. Thus, these four haplogroups point to a common population expansion, even though I2 (TMRCA, weighted ρ, 7,800 ya) and J2a (TMRCA, 5,500 ya) are older than R1b-DF27. It is worth noting that the expansion of these haplogroups happened after the TMRCA of R1b-DF27.

Sum up and discussion

We have characterized the geographical distribution and phylogenetic structure of haplogroup R1b-DF27 in W. Europe, particularly in Iberia, where it reaches its highest frequencies (40–70%). The age of this haplogroup appears clear: with independent samples (our samples vs. the 1000 genome project dataset) and independent methods (variation in 15 STRs vs. whole Y-chromosome sequences), the age of R1b-DF27 is firmly grounded around 4000–4500 ya, which coincides with the population upheaval in W. Europe at the transition between the Neolithic and the Bronze Age. Before this period, R1b-M269 was rare in the ancient DNA record, and during it the current frequencies were rapidly reached. It is also one of the haplogroups (along with its daughter clades, R1b-U106 and R1b-S116) with a sequence structure that shows signs of a population explosion or burst. STR diversity in our dataset is much more compatible with population growth than with stationarity, as shown by the ABC results, but, contrary to other haplogroups such as the whole of R1b-S116, G2a, I2 or J2a, the start of this growth is closer to the TMRCA of the haplogroup. Although the median time for the start of the expansion is older in R1b-DF27 than in other haplogroups, and could suggest the action of a different demographic process, all HPD intervals broadly overlap, and thus, a common demographic history may have affected the whole of the Y chromosome diversity in Iberia. The HPD intervals encompass a broad timeframe, and could reflect the post-Neolithic population expansions from the Bronze Age to the Roman Empire.

While when R1b-DF27 appeared seems clear, where it originated may be more difficult to pinpoint. If we extrapolated directly from haplogroup frequencies, then R1b-DF27 would have originated in the Basque Country; however, for R1b-DF27 and most of its subhaplogroups, internal diversity measures and age estimates are lower in Basques than in any other population. Then, the high frequencies of R1b-DF27 among Basques could be better explained by drift rather than by a local origin (except for the case of M153; see below), which could also have decreased the internal diversity of R1b-DF27 among Basques. An origin of R1b-DF27 outside the Iberian Peninsula could also be contemplated, and could mirror the external origin of R1b-M269, even if it reaches there its highest frequencies. However, the search for an external origin would be limited to France and Great Britain; R1b-DF27 seems to be rare or absent elsewhere: Y-STR data are available only for France, and point to a lower diversity and more recent ages than in Iberia (Table 3). Unlike in Basques, drift in a traditionally closed population seems an unlikely explanation for this pattern, and therefore, it does not seem probable that R1b-DF27 originated in France. Then, a local origin in Iberia seems the most plausible hypothesis. Within Iberia, Aragon shows the highest diversity and age estimates for R1b-DF27, Z195, and the L176.2 branch, although, given the small sample size, any conclusion should be taken cautiously. On the contrary, Z220 and Z278 are estimated to be older in North Central Spain (N Castile, Cantabria and Asturias). Finally, M153 is almost restricted to the Basque Country: it is rarely present at frequencies >1% elsewhere in Spain (although see the cases of Alacant, Andalusia and Madrid, Suppl. Table 1), and it was found at higher frequencies (10–17%) in several Basque regions; a local origin seems plausible, but, given the scarcity of M153 chromosomes outside of the Basque Country, the diversity and age values cannot be compared.

Within its range, R1b-DF27 shows same geographical differentiation: Western Iberia (particularly, Asturias and Portugal), with low frequencies of R1b-Z195 derived chromosomes and relatively high values of R1b-DF27* (xZ195); North Central Spain is characterized by relatively high frequencies of the Z220 branch compared to the L176.2 branch; the latter is more abundant in Eastern Iberia. Taken together, these observations seem to match the East-West patterning that has occurred at least twice in the history of Iberia: i) in pre-Roman times, with Celtic-speaking peoples occupying the center and west of the Iberian Peninsula, while the non-Indoeuropean eponymous Iberians settled the Mediterranean coast and hinterland; and ii) in the Middle Ages, when Christian kingdoms in the North expanded gradually southwards and occupied territories held by Muslim fiefs.

I wouldn’t trust the absence of R1b-DF27 outside France as a proof that its origin must be in Western Europe – especially since we have ancient DNA, and that assertion might prove quite wrong – but aside from that the article seems solid in its analysis of modern populations.

Related:

- Something is very wrong with models based on the so-called ‘steppe admixture’ – and archaeologists are catching up

- How to do modern phylogeography: Relationships between clans and genetic kin explain cultural similarities over vast distances

- Heyd, Mallory, and Prescott were right about Bell Beakers

Text and figures from the article, licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License. To view a copy of this license, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.