Open access African evolutionary history inferred from whole genome sequence data of 44 indigenous African populations, by Fan et al. Genome Biology (2019) 20:82.

Interesting excerpts (emphasis mine):

Introduction

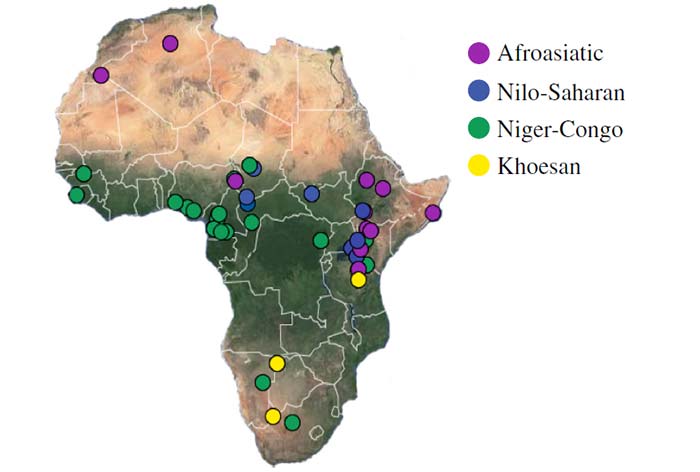

To extend our knowledge of patterns of genomic diversity in Africa, we generated high coverage (> 30×) genome sequencing data from 43 geographically diverse Africans originating from 22 ethnic groups, representing a broad array of ethnic, linguistic, cultural, and geographic diversity (Additional file 1: Table S1). These include a number of populations of anthropological interest that have never previously been characterized for high-coverage genome sequence diversity such as Afroasiatic-speaking El Molo fishermen and Nilo-Saharan-speaking Ogiek hunter-gatherers (Kenya); Afroasiatic-speaking Aari, Agaw, and Amhara agro-pastoralists (Ethiopia); Niger-Congo-speaking Fulani pastoralists (Cameroon); Nilo-Saharan-speaking Kaba (Central African Republic, CAR); and Laka and Bulala (Chad) among others. We integrated this data with 49 whole genome sequences generated as part of the Simons Genome Diversity Project (SGDP) [14] (…)

Results and discussion

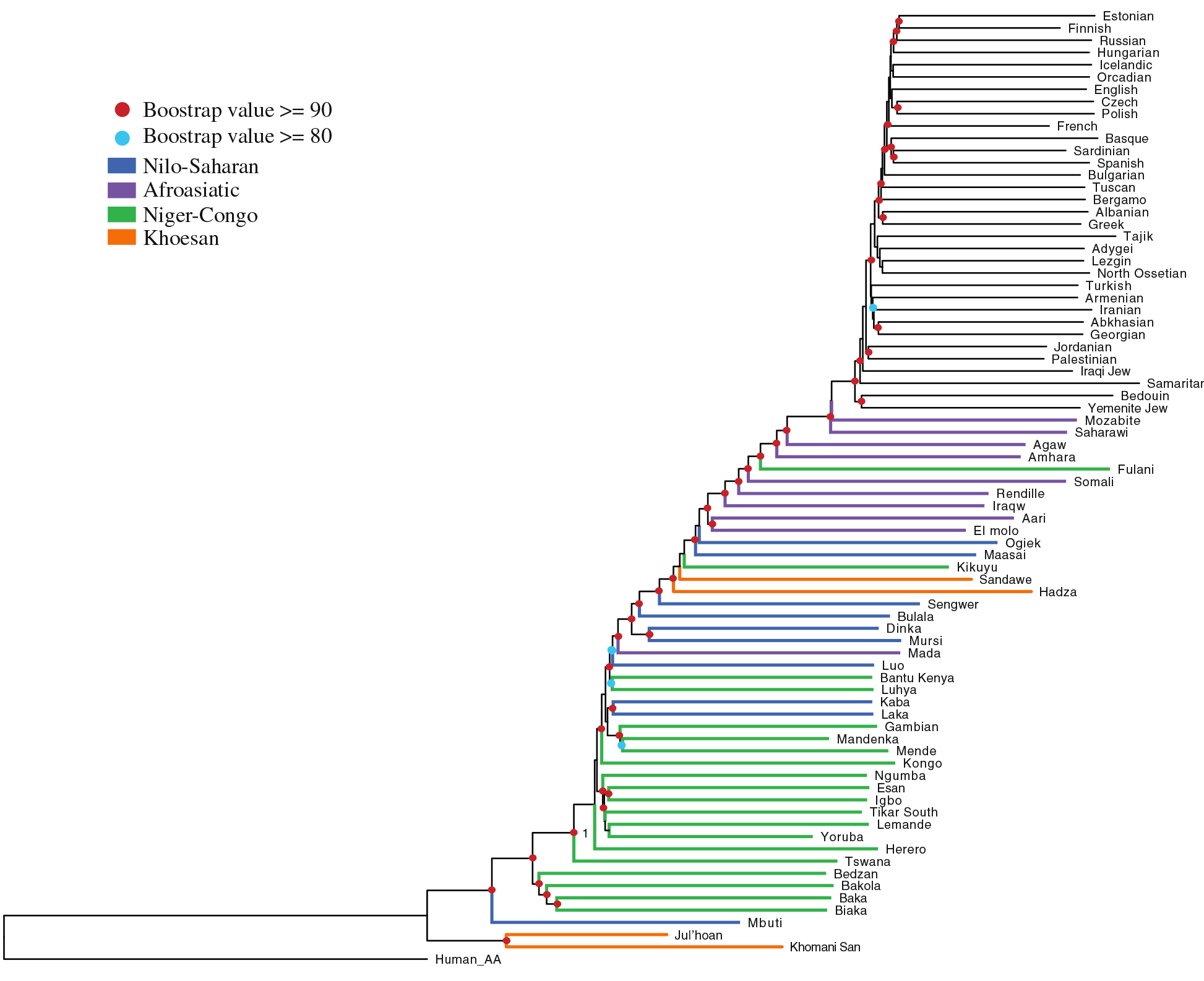

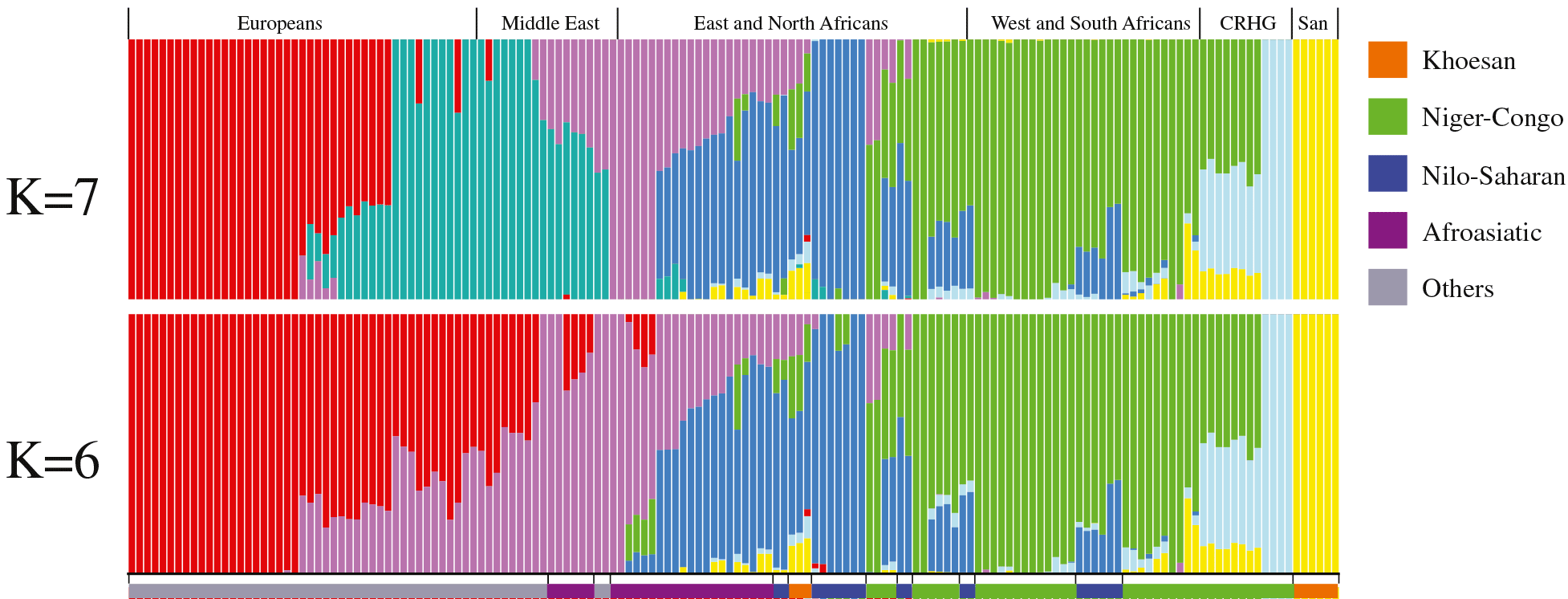

We found that the CRHG populations from central Africa, including the Mbuti from the Demographic Republic of Congo (DRC), Biaka from the CAR, and Baka, Bakola, and Bedzan from Cameroon, also form a basal lineage in the phylogeny. The other two hunter-gatherer populations, Hadza and Sandawe, living in Tanzania, group with populations from eastern Africa (Fig. 2). The two Nilo-Saharan-speaking populations, the Mursi from southern Ethiopia and the Dinka from southern Sudan, group into a single cluster, which is consistent with archeological data indicating that the migration of Nilo-Saharan populations to eastern Africa originated from a source population in southern Sudan in the last 3000 years [4, 23, 24, 25].

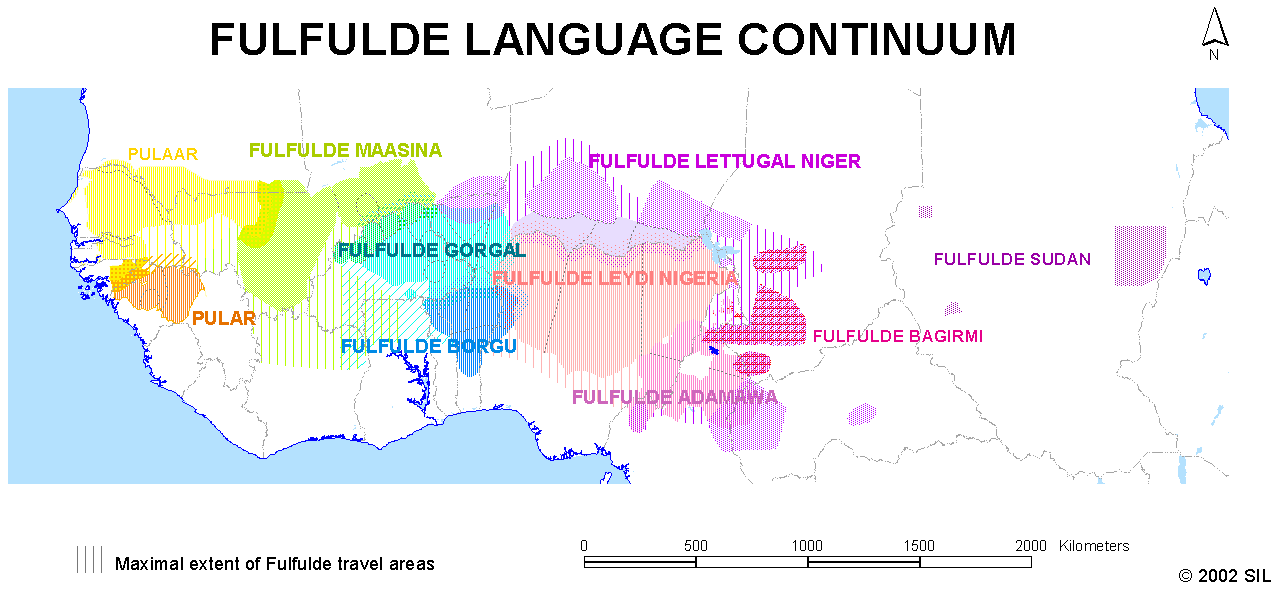

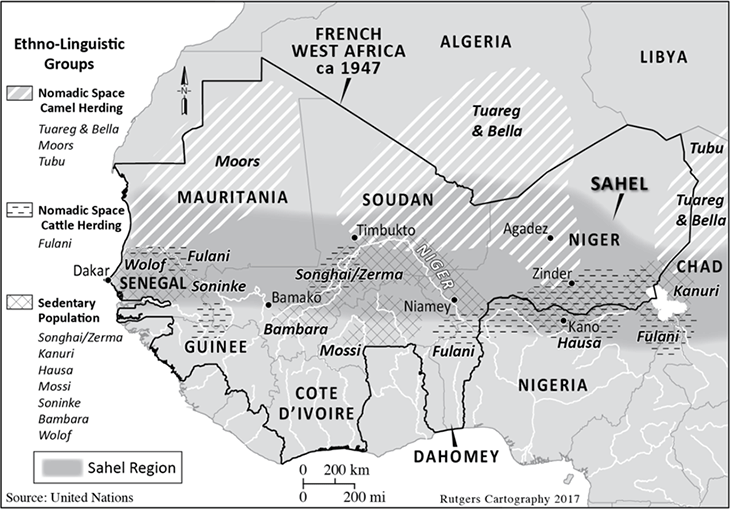

The Fulani people are traditionally nomadic pastoralists living across a broad geographic range spanning Sudan, the Sahel, Central, and Western Africa. The Fulani in our study, sampled from Cameroon, clustered with the Afroasiatic-speaking populations in East Africa in the phylogenetic analysis, indicating a potential language replacement from Afroasiatic to Niger-Congo in this population (Fig. 2). Prior studies suggest a complex history of the Fulani; analyses of Y chromosome variation suggest a shared ancestry with Nilo-Saharan and Afroasiatic populations [24], whereas mtDNA indicates a West African origin [26]. An analysis based on autosomal markers found traces of West Eurasian-related ancestry in this population [4], which suggests a North African or East African origin (as North and East Africans also have such ancestry likely related to expansions of farmers and herders from the Near East) and is consistent with the presence at moderate frequency of the −13,910T variant associated with lactose tolerance in European populations [15, 16].

Phylogenetic reconstruction of the relationship of African individuals under a model allowing for migration using TREEMIX [27] largely recapitulates the NJ phylogeny with the exception of the Fulani who cluster near neighboring Niger-Congo-speaking populations with whom they have admixed (Additional file 2: Figure S1). Interestingly, TREEMIX analysis indicates evidence for gene flow between the Hadza and the ancestors of the Ju|‘hoan and Khomani San, supporting genetic, linguistic, and archeological evidence that Khoesan-speaking populations may have originated in Eastern Africa [28, 29, 30].

About the Fulani, this is what the referenced study of Y‐chromosome variation among 15 Sudanese populations by Hassan et al. (2008), had to say:

- Haplogroups A-M13 and B-M60 are present at high frequencies in Nilo-Saharan groups except Nubians, with low frequencies in Afro-Asiatic groups although notable frequencies of B-M60 were found in Hausa (15.6%) and Copts (15.2%).

- Haplogroup E (four different haplotypes) accounts for the majority (34.4%) of the chromosome and is widespread in the Sudan. E-M78 represents 74.5% of haplogroup E, the highest frequencies observed in Masalit and Fur populations. E-M33 (5.2%) is largely confined to Fulani and Hausa, whereas E-M2 is restricted to Hausa. E-M215 was found to occur more in Nilo-Saharan rather than Afro-Asiatic speaking groups.

- In contrast, haplogroups F-M89, I-M170, J-12f2, and JM172 were found to be more frequent in the Afro-Asiatic speaking groups. J-12f2 and J-M172 represents 94% and 6%, respectively, of haplogroup J with high frequencies among Nubians, Copts, and Arabs.

- Haplogroup K-M9 is restricted to Hausa and Gaalien with low frequencies and is absent in Nilo-Saharan and Niger-Congo.

- Haplogroup R-M173 appears to be the most frequent haplogroup in Fulani, and haplogroup R-P25 has the highest frequency in Hausa and Copts and is present at lower frequencies in north, east, and western Sudan.

- Haplogroups A-M51, A-M23, D-M174, H-M52, L-M11, OM175, and P-M74 were completely absent from the populations analyzed.

This is what David Reich will talk about in the seminar Insights into language expansions from ancient DNA:

In this talk, I will describe how the new science of genome-wide ancient DNA can provide insights into past spreads of language and culture. I will discuss five examples: (1) the spread of Indo-European languages to Europe and South Asia in association with Steppe pastoralist ancestry, (2) the spread of Austronesian languages to the open Pacific islands in association with Taiwanese aboriginal-associated ancestry, (3) the spread of Austroasiatic languages through southeast Asia in association with the characteristic ancestry type that is also represented in western Indonesia suggesting that these languages were once widespread there, (4) the spread of Afroasiastic languages through in East Africa as part of the Pastoral Neolithic farming expansion, and (5) the spread of Na-Dene languages in North America in association with Proto-Paleoeskimo ancestry. I will highlight the ways that ancient DNA can meaningfully contribute to our understanding of language expansions—increasing the plausibility of some scenarios while decreasing the plausibility of others—while emphasizing that with genetic data by itself we can never definitively determine what languages ancient people spoke.

EDIT (3 MAY 2019): Apparently, there was not much to take from the talk:

DR: finally talks about spread of afroasiatic languages in northern Africa. Shows a complicated model. Idk man there's a lot of populations.

— Joshua G. Schraiber? (@jgschraiber) May 2, 2019

This seminar (and maybe some new paper on the Neolithic expansion in Africa) could shed light on population movements that may be related to the spread of Afroasiatic dialects. Until now, it seems that Bantu peoples have been more interesting for linguistics and archaeology, and South and East Africans for anthropology.

Archaeology in Africa appears to be in its infancy, as is population genomics. From the latest publication by Carina Schlebusch, Population migration and adaptation during the African Holocene: A genetic perspective, a chapter from Modern Human Origins and Dispersal (2019):

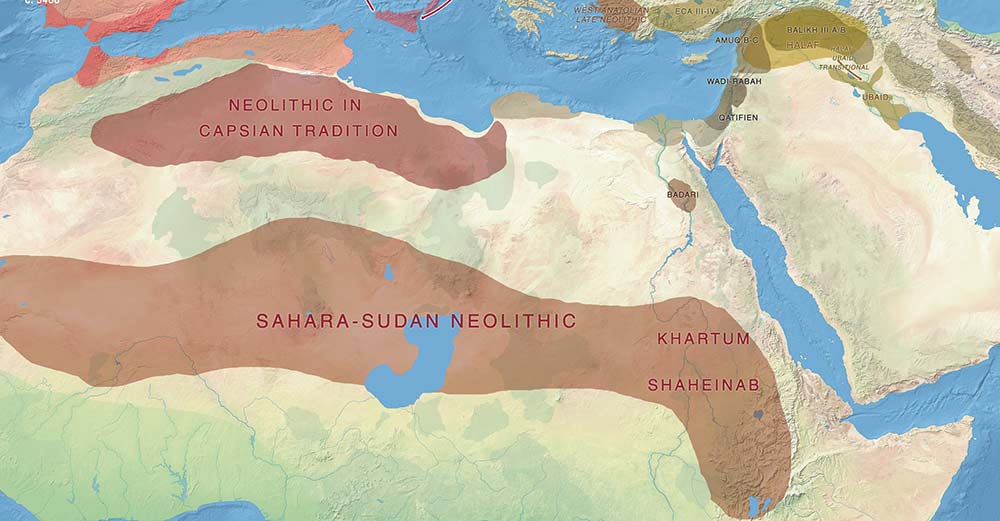

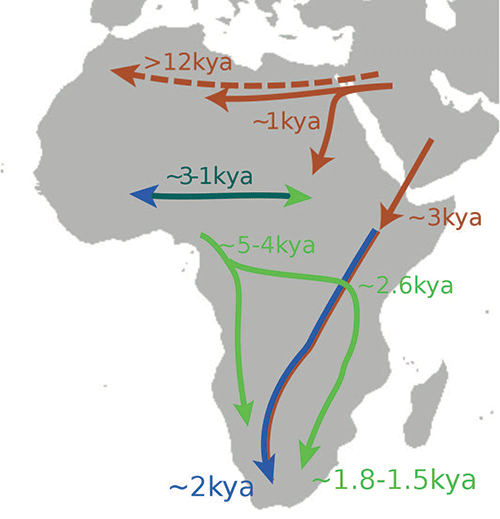

The process behind the introduction and development of farming in Africa is still unclear. It is not known how many independent invention events there were in the continent and to which extent the various first instances of farming in northern Africa are linked. Based on the archeological record, it was proposed that at least three regions in Africa may have developed agriculture independently: the Sahara/Sahel (around 7 ka), the Ethiopian highlands (7-4 ka), and western Africa (5-3 ka). In addition to these developments, the Nile River Valley is thought to have adopted agriculture (around 7.2 ka), from the Neolithic Revolution in the Middle East (Chapter 12 – Jobling et al. 2014; Chapter 35, 37 – Mitchell and Lane 2013). From these diverse centers of origin, farmers or farming practices spread to the rest of Africa, with domesticate animals reaching the southern tip of Africa ~2 ka and crop farming ~1,8 ka (Mitchell 2002; Huffman 2007)

Similar to the case in Europe and the 1990s-2000s wrong haplogroup history based on the modern distribution of R1b, R1a, N, or I2, it is possible that neither of the most often mentioned haplogroups linked to the Afroasiatic expansion, E and J, were responsible for its early spread within Africa, despite their widespread distribution in certain modern Afroasiatic-speaking areas. The fact that such assessments include implausible glottochronological dates spanning up to 20,000 years for the parent language, combined with regional language continuities despite archaeological changes, makes them even more suspicious.

Similar to the case with Indo-Europeans and the “steppe ancestry” concept of the 2010s, it may be that the often-looked-for West Eurasian ancestry among Africans is the effect of recent migrations, unrelated to the Afroasiatic expansion. The results of this paper could be offering another sign of how this ancestry may have expanded only quite recently westwards from East Africa through the Sahel, after the Semitic expansion to the south:

1. From approximately 1000 BC, accompanying Nilo-Saharan peoples.

2. From approximately AD 1500, with the different population movements related to the nomadic Fulani:

- Arguably, since the Fulani caste system wasn’t as elaborate in northern Nigeria, eastern Niger, and Cameroon, these specific groups would be a good example of the admixture with eastern populations, based on the (proportionally) huge amount of slaves they dealt with.

- Similarly, it could be argued that the castes-based social stratification in most other territories (including Sudan) would have helped them keep a genetic make-up similar to their region of origin in terms of ancient lineages, hence similar to Chadic populations from west to east.

Reich’s assertion of the association of the language expansion with the spread of Pastoral Neolithic is still too vague, but – based on previous publications of ancient DNA in Africa and the Levant – I don’t have high hopes for a revolutionary paper in the near future. Without many samples and proper temporal transects, we are stuck with speculations based on modern distributions and scarce historical data.

About the potential genetic make-up of Cameroon before the arrival of the Neolithic, from the recent SAA 84th Annual Meeting (Abstracts in PDF):

Lipson, Mark (Harvard Medical School), Mary Prendergast (Harvard University), Isabelle Ribot (Université de Montréal), Carles Lalueza-Fox (Institute of Evolutionary Biology CSIC-UPF) and David Reich (Harvard Medical School)

[253] Ancient Human DNA from Shum Laka (Cameroon) in the Context of African Population History We generated genome-wide DNA data from four people buried at the site of Shum Laka in Cameroon between 8000–3000 years ago. One individual carried the deeply divergent Y chromosome haplogroup A00 found at low frequencies among some present-day Niger-Congo speakers, but the genome-wide ancestry profiles for all four individuals are very different from the majority of West Africans today and instead are more similar to West-Central African hunter-gatherers. Thus, despite the geographic proximity of Shum Laka to the hypothesized birthplace of Bantu languages and the temporal range of our samples bookending the initial Bantu expansion, these individuals are not representative of a Bantu source population. We present a phylogenetic model including Shum Laka that features three major radiations within Africa: one phase early in the history of modern humans, one close to the time of the migration giving rise to non-Africans, and one in the past several thousand years. Present-day West Africans and some East Africans, in addition to Central and Southern African hunter-gatherers, retain ancestry from the first phase, which is therefore still represented throughout the majority of human diversity in Africa today.

Related

- Sahara’s rather pale-green and discontinuous Sahelo-Sudanian steppe corridor, and the R1b – Afroasiatic connection

- Genetic history of admixture across inner Eurasia; Botai shows R1b-M73

- Steppe and Caucasus Eneolithic: the new keystones of the EHG-CHG-ANE ancestry in steppe groups

- Ancient genomes from North Africa evidence Neolithic migrations to the Maghreb

- Tales of Human Migration, Admixture, and Selection in Africa

- Pleistocene North African genomes link Near Eastern and sub-Saharan African human populations

- Genetic ancestry of Hadza and Sandawe peoples reveals ancient population structure in Africa

- R1b-V88 migration through Southern Italy into Green Sahara corridor, and the Afroasiatic connection

- Potential Afroasiatic Urheimat near Lake Megachad

- Expansion of peoples associated with spread of haplogroups: Mongols and C3*-F3918, Arabs and E-M183 (M81)

- The arrival of haplogroup R1a-M417 in Eastern Europe, and the east-west diffusion of pottery through North Eurasia

- Genetic landscapes showing human genetic diversity aligning with geography

- Human ancestry solves language questions? New admixture citebait